|

|

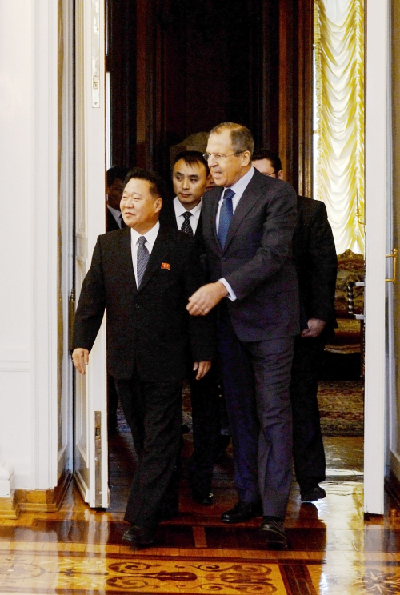

CLOSER EMBRACE: Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov meets with Choe Ryong Hae, special envoy of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, in Moscow on November 20 (JIA YUCHEN) |

Choe Ryong Hae, a close aide of Kim Jong Un, top leader of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK)—also known as North Korea—visited Russia in November as a special envoy of Kim.

Choe, a member of the Presidium of the Political Bureau and Secretary of the Central Committee of the Worker's Party of Korea, met with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Kremlin and passed along a message from Kim. The two sides also committed to taking steps to raise the level of their political dialogue and finding ways to intensify economic and military cooperation. Most notably, the two sides also discussed how to restart the six-party talks on the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue and foster a favorable environment. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that Pyongyang is preparing to restart the talks without preconditions.

Now, it is still difficult to judge whether the major objective of Choe's Moscow trip was to discuss restarting the six-party talks or if Pyongyang just passively accepted Russia's suggestion to engage in the talks for its own aims. In any case, the move shows that the settlement of the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue cannot bypass the talks.

Suspended dialogue

The six-party talks, starting in August 2003 in Beijing, involve North Korea, the United States, China, Russia, the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea) and Japan. Since North Korea pulled out of the talks in April 2009, the situation on the Korean Peninsula has come to a stiff deadlock. Pyongyang firmly upholds a strategy of developing nuclear weapons while pursuing economic growth. Thus, it is even more difficult for the country to give up its nuclear program.

That being the case, the United States has begun to intentionally ignore North Korea, as it is more concerned with the overall global situation. Although President Barack Obama announced shifting U.S. strategic focus to the Asia-Pacific region, turmoil in other part of the world, especially unrest in the Middle East, has distracted him from this objective. At the same time, the Obama administration is also facing numerous domestic troubles. Thus, there is no urgent need for it to invest efforts into the stubborn Korean Peninsula nuclear issue.

In addition, the U.S. pivot-to-Asia strategy also requires a military presence in the region. The protracted Korean Peninsula nuclear issue provides an excuse for the United States to strengthen its regional military might. It promotes the construction of a U.S.-Japan-ROK military alliance so as to have more leverage to confine the development of the China-South Korea strategic cooperative partnership.

Under these circumstances, Pyongyang has tried and failed many times to find opportunities to talk bilaterally with Washington.

DPRK authorities have attempted to repeat the story of the 2002 North Korea-Japan summit that prompted the United States to engage in dialogue with them. But times have changed, and it would be impossible for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to visit North Korea given U.S. opposition.