|

|

|

(CFP) |

In a typical hot summer in China, investors never felt chillier amid a rout in the stock market.

On June 24, the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index plummeted 5.3 percent, the biggest single-day slump in four years, to 1,963.24 points. The next day, Chinese stocks touched a four-and-a-half-year low before a late rally. The steep decline marked the first time since January 2009 that the Shanghai Composite Index had fallen below 1,900 points.

The markets tumbled because of mounting concerns over an exacerbating credit crunch in China's banking system amid the central bank's hawkish stance to not inject as much liquidity as Chinese commercial banks had gotten accustomed to.

The liquidity squeeze in the banking sector is best evidenced by a sharp spike in interbank lending rates since mid-May. On June 20, the Shanghai interbank overnight rate, a gauge of interbank borrowing costs, climbed to a record high of 13.44 percent.

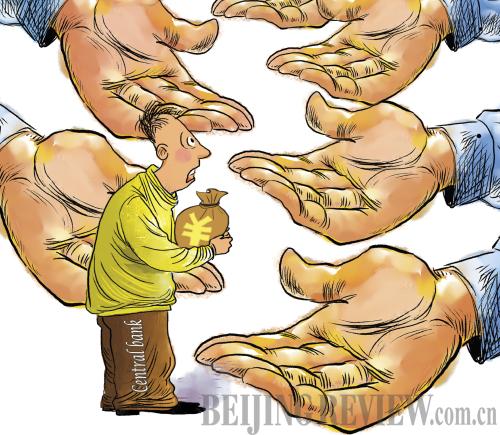

As usual, commercial banks turned to the People's Bank of China (PBC), the country's central bank, for help, only to find the central bank turned its back on the distress. On June 24, the central bank urged commercial banks to control for risks associated with credit expansion and manage their liquidity.

To cushion the impact from the global financial crisis in 2008, China unleashed a monetary stimulus package in an attempt to prevent the economy from being dragged down. And the government-led credit boom has been one of the key contributors to China's economic growth in recent years. However, an explosive credit boom was coupled by mounting risks, which became a ticking time-bomb threat to the world's second largest economy.

This time, the PBC wants to rein in excess bank lending, especially in the sector of shadow banking—all non-bank loans that involve banks and trust companies, underground finance, micro-credit companies, private financing, private-equity investment, hedge funds and off-balance sheet lending transactions. China's shadow banking system has lent far too much and too recklessly over the past several years. Excessive amounts of debt have been accumulated by speculators, property developers and local governments. The PBC wants to push money instead into the real economy as it seeks to shore up growth.

Experts warn that without thorough reform of the country's banks, the entire financial system could face its biggest crisis yet.

The real reason

June is a traditional season for a liquidity crunch, but this year's situation was worse. A source from the PBC told Xinhua News Agency that several specific factors contributed to the tightness. "First, bank loans rocketed in the past several months, causing liquidity pressure on commercial banks. Second, the end of May is the traditional peak season for corporate tax payments. Third, a recent regulation on the foreign exchange market to clamp down on capital inflows has made China suffer from a drop in foreign exchange inflows in recent weeks and months.

But do banks really lack cash? The answer is no.

As of June 21, financial institutions had total provisions of 1.5 trillion yuan ($242 billion). Usually, provisions of 600 billion to 700 billion yuan ($97.62 billion to $113.89 billion) could meet the needs of daily banking transactions, according to a PBC statement on its website.

Capital in most Chinese banks flows in four directions: required reserves against savings, the repo of the central bank, loan disbursal and the purchase of money management products.

Right now, China's commercial banks have 19 trillion yuan ($3.09 trillion) stored in the central bank as reserves against deposits, so ordinary people don't need to worry that how the liquidity squeeze would affect their deposits. The most worrying are bank loans and money management products.

A source told Securities Times that bank loans from China's "big four" state-owned commercial banks—namely the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China and China Construction Bank—totaled 217 billion yuan ($35.3 billion) from June 1 to 9, surpassing the total loans from the four banks in May and far exceeding their loans in June 2012.

At the end of each June, the central bank would inspect the liquidity risk at all commercial banks. That's when banks withdraw their money. In the past, banks managed to raise the money by all means to cope with the central bank's inspection. But this year has been difficult due to a strong U.S. dollar and a large amount of cash flow out of emerging markets and to the United States. They can only borrow from other banks.

"The liquidity crunch is not because of a money supply shortfall, but because of the unreasonable structure of commercial banks' capital spending," said Guo Tianyong, Director of the Banking Research Center at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing.

Guo said that the cash squeeze is a good lesson for Chinese banks, but there is no need to compare with the Lehman-related freezing of interbank liquidity in the United States in 2008 because the two are totally different in nature.

"The crisis in the U.S. banks in 2008 derived from loan disbursal in breach of regulations," said Guo. "For instance, they gave bank loans to unqualified applicants and leveraged those housing mortgages. Later, the homeowners couldn't repay their debt, which resulted in the subprime mortgage crisis. But in China, housing mortgages only account for 25 percent of the total bank loans, and there is no leverage in that," said Guo.

Guo's viewpoint was echoed by Stephen Green, chief China economist at Standard Chartered Bank.

"China's current high interbank rates are the intended result of a PBC campaign to force banks to better manage liquidity and deleverage from certain sectors," said Green.

"We believe it is a deliberate policy meant to de-risk the interbank system," he said.

|