|

|

|

(Left) A brother and his sister in their native village located in Ankang, northwest China's Shaanxi Province, on May 22, 2014

(Right) The parents of the two siblings in Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province, where they live and work, on May 28, 2014 (XINHUA) |

Four young siblings, the youngest just 5 and the oldest 13, were found dead at home in a village in southwest China's Guizhou Province on June 9. Initial reports said they had killed themselves by drinking pesticide.

Police found a note written by the teen. "Thanks for your kindness. I know you mean well for us, but we should go now," said the note, apparently written to the parents. "I once swore to live no longer than 15, and death has been my dream for years."

Tragic farewell

The teen brother and his three sisters were from Qixingguan District of Cizhu Village in Bijie of Guizhou, one of the poorest areas in the mountainous province. After their mother left home in early 2014, followed by their father this March, the quartet lived by themselves without any adult supervision. Cooped up in a cluttered, dusty house, they refused to admit visitors and stopped going to school one month before the tragedy.

At first, many media outlets portrayed the suicides as the tragedy of children from a poor family who couldn't afford food and were driven to make such a desperate choice. But when reporters went to the village, they found a different story. The three-storied house had ample food stocks: 500 kg corn flour and 25 kg preserved meat. Also, the children had a bank card with a balance of 3,500 yuan ($560). Their father, Zhang Fangqi, had given it to them and was sending money periodically.

"The children did not lack food and clothes, but the love and care of parents," said Xiao Wenying, a distant relative of the family. "The parents failed to fulfill their responsibilities."

"The siblings' grandparents had passed away and the kids often skipped class before dropping out of school," said Pan Ling, another relative.

The mother, Ren Xifen, left home reportedly due to domestic abuse by her husband, going to work with a toy company in south China's Guangdong Province. Since then, she had called the children just once. The father couldn't be reached even after the tragedy.

"It was desperation and loneliness that killed the kids rather than poverty," said Sun Xuemei, a journalist from the Beijing Times newspaper.

The news of the suicides soon went viral online and triggered widespread sympathy and anger.

"How come the parents leave four kids at home and don't even bother to make a call?" said a 34-year-old Beijinger claiming to be a mother of two children. "They don't deserve to be parents."

Some blamed the local government and school for doing nothing when the four didn't show up in class for a month.

"To put all the blame on the parents, local government and school is not rational," said Ye Jingzhong, a professor from China Agricultural University who has studied youngsters left behind in rural areas for more than 10 years. "They are not the root cause of the tragedy."

"In the past two decades, rural people were encouraged to go to big cities. For a long time, this was regarded as a win-win solution as they earned money and urban construction got a boost. But problems have shown up in recent years," said Ye.

"Zhang, the father of the kids in the tragedy, is a left-behind kid himself. He is of the first generation of left-behind children," said Yu Qiwen, founder of Parents Heart Foundation, an NGO caring for left-behind children. "What we should consider is, how come a left-behind child who experienced a miserable separation from his parents left his own kids to the same misery? If we don't take proper action, this tragedy will most probably be passed on to the next generation."

Yu explained what he meant by "proper": "We have thousands of NGOs for left-behind children but their effects have not been ideal so far. Because most people don't know or don't care what these kids really need, they just make assumptions. Many think the main thing is money, so they just donate money. But what the kids need more is company, spending time together."

|

|

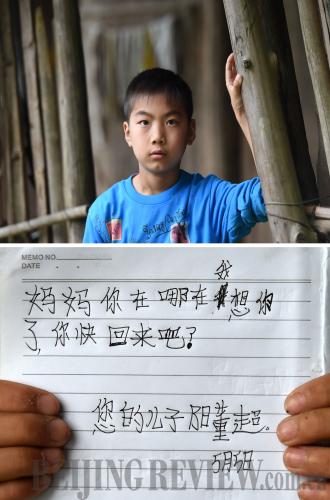

"Mom, where are you? I miss you, please come back home soon!"—Ten-year-old Yang Dongchao in Dongsheng Village of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region writes a letter to his mom, who has been gone ever since he was 3 months old (XINHUA) |

The efforts

Yu, a former businessman, decided to set up Parents Heart Foundation after he heard a sad report about five youngsters in Bijie.

In November 2012, five left-behind children, aged between 9 and 13, were found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning inside a dustbin where they had crept in to keep themselves warm by lighting a fire.

"I was driving when I heard the news," said Yu. "I couldn't help my tears. I couldn't believe it was real and couldn't imagine how helpless those kids must have been in the dustbin."

In early 2013, Yu founded Parents Heart Foundation with his friends and since then, he has been to Bijie for more than 30 times. In 2013, the NGO launched Candlelight Action, employing teachers in remote and poor areas to teach music, sports, and the fine arts to children and give them company on weekends.

By December 31, 2014, there were four candlelight primary schools in Guizhou, benefiting 1,116 students. This year, they plan to set up more schools.

"When moms leave hometown, leaving their children behind, the kids wonder where mom is. If possible, mothers should take their kids with them, then it would be 'home is where mom is.' But if the mother doesn't take her kids along, who is going to be the surrogate mom?" Yu asked. The NGOs' function is to be mom when this situation arises. "It takes time, energy and most importantly, love," he added.

Du Shuang is Director of Growing Home, an NGO set up in 2008 to educate boarders in rural schools.

"It needs a long time for a volunteer to understand the world of left-behind children," said Du, a psychology consultant for 17 years. "But most volunteers don't stay that long. This has made psychological help for left-behind children untenable."

In 2001, the Central Government decided to optimize educational resources, merging small village schools into larger ones located in more populous regions. The number of primary schools in rural areas thus decreased dramatically. More than 300,000 primary and middle schools in rural areas were merged and more than 30 million students relocated to the new schools as boarders.

On April 20, the 21st Century Education Research Institute, a Beijing-based organization researching educational problems from an independent perspective, released a report, the 2015 Education Blue Paper, which said there are far more boarding students in disadvantaged areas than in urban areas.

Over 60 percent of rural schools have 50 to 300 boarders, with left-behind children accounting for 56.3 percent of them.

Due to the monotonous boarding life, poverty and absence of parental care, left-behind children show more psychological difficulties than their urban peers in terms of personality, temper and interpersonal relationships.

Incidents of running away, cutting classes, theft, destruction of property and cheating by left-behind children are two to three times higher than those among urban children.

The merging of schools, according to Ye with China Agricultural University, might be another reason for the rising problem of left-behind children.

"Before, almost every village had its own school; now the kids have to either walk a long way to [their new] school or be boarders," Ye explained. "The scene of groups of kids running in or out of school every day has disappeared, making villages quieter and more desolate."

Picture of loneliness

In 2011, Liu Jie, a Xinhua News Agency photographer, took a series of photographs titled Empty Stools. In the photographs, each village family laid a line of stools equaling the number of family members. However, most of the stools were empty as the adults had all left, leaving behind only the old and young, who sat on the stools and took the "family picture" with the empty stools.

In 2014, a documentary on left-behind children by renowned movie director Zhang Yimo was released. Stories Through 180 Lenses was edited out of the footage shot by left-behind children themselves, with the sponsored small DV cameras. Asked "Who are you living with?" almost all of them replied: "My grandparents."

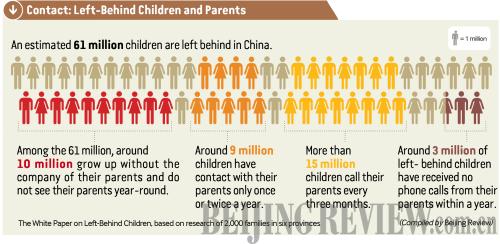

On June 18, the Beijing Children's Mental Health Care Center issued a white paper on the psychological conditions of left-behind children. It is based on research of 2,000 families, focusing on the rural areas of Guizhou, Shandong, Hebei, Gansu, Yunnan provinces and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

The report said of the estimated 61 million left-behind children, around 10 million, or 15.1 percent, are growing up without their parents and are unable to reunite with them so much as once a year, even during the Spring Festival, the most important occasion for family reunions in China.

About 4.3 percent have received no phone calls from their parents in a year. Around 9 million children come in contact with their parents once or twice a year. More than 15 million children call their parents only every three months.

The white paper warns that children unable to meet their parents at least once every three months have a higher possibility of experiencing mental problems. Also, children in northwest China have a higher chance of suffering mental problems than their peers in the eastern part of the country.

The problem is particularly prevalent in China's poorest regions. Families in the northwest were identified as being most at risk followed by those in the southwest. The prosperous eastern coastal region was affected the least.

The report also said girls are at a higher risk of having mental problems than boys as they tend to be "more sensitive, cautious and introvert," and less able to express their trauma.

The survey was made by a non-profit organization, On the Way to School, and a group of psychologists led by Professor Li Yifei from Beijing Normal University.

"We may not be able to help the children directly, but through the impact of the media, the community and by mobilizing resources, we can bring about indirect change," said Li, who is also the author of the report. "These children need mental nourishment just as much as material donations."

Copyedited by Sudeshna Sarkar

Comments to yuanyuan@bjreview.com |