|

Lastly, the battle over global rules has intensified. At the beginning of 2013, the United States and Europe promptly started talks on Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). In the Asia-Pacific region, the United States is resolutely trying to reach a consensus on Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with 11 countries, which excludes China. Asian countries have been committed to the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement. At the same time, negotiations on free trade areas are being held exuberantly across the world.

Talks on TPP and TTIP, which are described as "21st-century" agreements by the United States, are likely to be wrapped up in 2014, and related rules and scopes are more inclusive than that of the WTO. Once they come into effect, the United States and Europe intend to use them as a model for future WTO agreements, which will exert great pressures on non-member countries.

Risks remain

In 2014, economic globalization as well as regional economic integration will keep deepening, and international competition will become increasingly fiercer in the formulation of the rules. The world economy will bottom out and maintain moderate growth, and changes will take place in north-south development pattern.

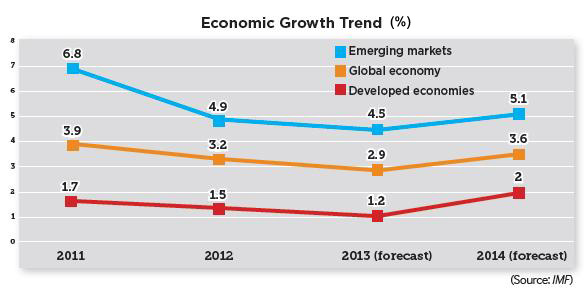

After two years of slowed growth, the world economy will grow and speed up on a larger scale. Many countries will see a turnaround, and even the debt-stricken southern European economies will stop contracting and begin to rebound. Of 198 economies, only four small economies will experience contraction, according to estimates by the IMF. The world economy is expected to expand by 3.6 percent, with developed and emerging economies growing by 2 percent and 5.1 percent respectively, coinciding with the predictions of the OECD.

As the European Commission forecasted, the eurozone will see its economy expand by 1.1 percent, and even sluggish Greece will register a slight growth of 0.6 percent. Generally speaking, emerging economies—India, Brazil and Russia in particular—will grow slower than before the eruption of the financial crisis, but this doesn't mean storms like the Asian financial crisis will be repeated. Changes are certain to take place in the market structures and development modes of emerging markets.

Since the financial crisis broke out in 2008, emerging markets have contributed over 70 percent to the global growth. Despite the current deceleration, this cannot be underestimated. As the IMF suggested, though the emerging markets and the developing world would slow down to 4.5 percent in 2013, they will account for 69 percent of global economic growth (based on purchasing power parity), or 85 percent (based on the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar). In 2014, the developed world, for the first time, will contribute more than half, or roughly 54 percent, to global growth. However, if calculated in purchasing power parity terms, the rate will drop to 35 percent.

Without a doubt, developed countries will rise in the near future, but will remain plagued by weak domestic demand, government debts and high unemployment. As a result of the overheated economic expansion and economic transformation, emerging economies will go through a deceleration period, but will still grow faster than the former.

In addition, another round of globalization may sweep across the world. After the crisis, regional economic integration has gained renewed prominence. Since the new WTO Director-General, Roberto Carvalho de Azevedo, took office, the "early harvest" agreement has been reinitiated, and the Doha round has made a historical breakthrough with the member economies agreeing on the Bali Package. Meanwhile, negotiations on service trade and information technology treaties are under way. All these indicate people are getting tired of bilateral or regional free trade arrangements that lead to a fragmented global market, and are shifting to multilateral cooperation.

According to a study by the OECD, the WTO "early harvest" agreement will help developing and developed countries grow by 10 percent and 5 percent respectively. A report from the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that the above-mentioned treaties, once effective, will add nearly $1 trillion to global trade volume, creating 21 million jobs, 18 million of which will be in the developing world.

Uncertainties will persist. First, the U.S. Fed is bound to exit QE policies step by step, and the wave of capital withdrawals from the emerging markets will cause continuous financial fluctuations and risks. Second, as Abenomics fades away and consumption tax rises, Japan's economy will fall back with possible debt problems and systematic banking risks. Third, the U.S. dollar will become stronger as a result of the Fed's QE exit; global commodity prices may continue to drop, resulting in capital chain ruptures of the emerging resource exporting countries.

The author is Director of the Institute of World Economic Studies under the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations

Email us at: yushujun@bjreview.com

|