|

|

|

COURTESY OF KENNETH LIEBERTHAL |

Amid turbulent times for China-U.S. relations, China expert Kenneth Lieberthal, Director of the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution, appeared March 3 in a live Web chat, answering questions from Beijing Review and an Ineternet audience on issues related to bilateral relations. Excerpts follow:

Deputy Secretary of State James Steinberg and senior White House Asia adviser Jeffrey Bader have landed in Beijing on a mission to patch up ties with China. Is there any specific consideration about the timing? What are your expectations for this visit?

Kenneth Lieberthal: Recent months have obviously seen a rough patch in U.S.-China relations. There are opportunities coming up to put things back on a steadier path. These include the Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED) and a possible return visit by [Chinese President] Hu Jintao to Washington sometime in late spring or early summer.

At the same time, Iran and other issues are sufficiently important to warrant some serious, high-level direct discussion. Steinberg and Bader are exceptionally knowledgeable about the U.S.-China relationship, and are critical to the policy process on China in Washington, D.C. I suspect their visit is to talk things through, and to try to work out how to make progress on the most critical issues that require U.S.-China cooperation. This is likely to be done in the context of preparing for the S&ED and for Hu's prospective visit.

|

|

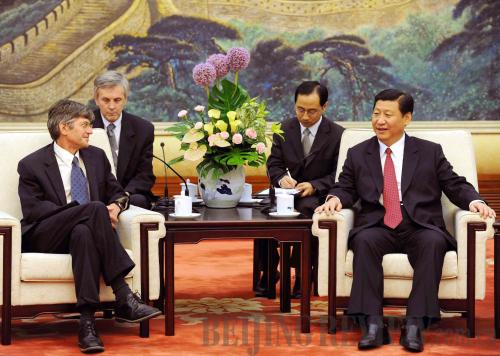

TALKING COMMON CONCERNS: Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping (right) meets with U.S. Deputy Secretary of State James Steinberg in Beijing on September 29, 2009 (RAO AIMIN) | There has been a lot of talk lately about what the United States has done to exacerbate tensions with China: speaking out on Internet freedom, the Dalai Lama's meeting with President Obama, the issuance of statements on the renminbi-dollar exchange rate, among other things. Should these be perceived as a change in the U.S. approach to China post-Copenhagen, or simply a coincidental confluence of events that stirred the pot a bit?

It is, I believe, a misconception to see America's policy toward China as having toughened suddenly in 2010. President Obama came into office with a very pragmatic approach to China. He saw U.S.-China cooperation—or at least our not undercutting each other—could be important to handling major global issues more effectively. Having no past experience with China, he was determined to spend much of 2009 establishing the basis for a very good working relationship with Hu Jintao and other Chinese leaders. That entailed, among other things, postponing decisions that inevitably would raise tensions such as the approval of arms sales to Taiwan, where those decisions could be put back for a period of months without doing harm to other interests.

But the United States informed the Chinese very clearly during 2009 that early in 2010 we would be making some of those decisions. For example, in his November trip to Beijing in 2009, President Obama directly told Hu Jintao that Obama would see the Dalai Lama in early 2010. It is, therefore, incorrect to see these 2010 decisions as a change in U.S. policy.

Is it possible that the Obama administration take a stronger stand with China on human rights and trade issues?

The Obama administration declared early on that it sees a number of issues as of major importance in U.S.-China relations. These include human rights and economic and trade issues. I think the important point is that the administration should remain consistent in its approach to these issues. Basic American policies in these areas are designed to promote—within reasonable boundaries—our values and our interests. There is no reason to shift to a stronger stand on either of these issues now—our current approach builds in flexibility to key concrete actions to developments in China and in our relationship with Beijing.

|