|

|

|

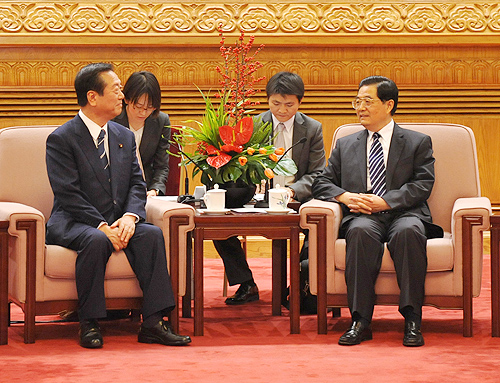

PARTY DIPLOMACY: Chinese President Hu Jintao meets a delegation of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) led by DPJ Secretary General Ichiro Ozawa in Beijing on December 10 (RAO AIMIN) |

Led by Ichiro Ozawa, Secretary General of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the 16th delegation of the Great Wall Program arrived in China in early December for a groundbreaking visit. Indeed, while attracting momentous attention in both countries, it was also hailed as a success.

There are several reasons why. For one thing, this delegation was the first led by Ozawa—a longtime proponent of the program—since the DPJ's sweeping victory in parliamentary elections in August.

Since its inception, the DPJ has always lent great importance to Japan's relations with China. Moreover, since Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama took office on September 16, Beijing and Tokyo have actively engaged to improve ties.

This round of diplomacy set a number of precedents, too. To begin with, Ozawa was already a renowned politician within his party and in Japan.

Beyond that, however, the sheer size of the delegation itself was remarkable. With 143 sitting members of parliament and nearly 500 individuals from all walks of Japanese society, this group carried more representation than any previous delegation.

Sweetening the pot was the fact that, among the 143 parliamentarians, some 80 were newly elected.

Beyond these factors, the fact that Ozawa's office selected the delegation itself is also significant. In particular, he encouraged newly elected DPJ parliamentarians to join in. Perhaps surprisingly, many of the new parliament members had never visited China before. It is thus no exaggeration to say that the application process was a competitive one.

The rich schedule of the visit itself was another signal of success. Apart from traditional places of interest—including the Forbidden City and the Great Wall—the visitors also toured the China Disabled People's Performing Arts Troupe and the Beijing Children's Palace.

The Japanese guests also got a close look at the modernization underway in China. Other stops included the Beijing Urban Rail Transport Command Center, the Gaobeidian Sewage Treatment Plant, the Yizhuang Economic and Technological Development Area and China's Silicon Valley Zhongguancun, among other sites.

The group, in addition, journeyed to rural and urban communities to meet with ordinary Chinese people. The parliamentarians expressed strong impressions of an increasingly prosperous, empowered China.

Tokyo's overall purpose was to deliver one single, undeniably clear message—that the DPJ strongly values its relations with Beijing.

It is one with a considerable legacy. Since its foundation in 1998, the DPJ has shared good relations with the Communist Party of China (CPC). Before taking power, DPJ members had also promoted exchanges with the CPC. This visit, of course, will further cement already strong relations.

But in addition to the DPJ's desire for mutual goals, it also has domestic motivations afoot—namely, containing its opponents in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

Following the birth of the Hatoyama cabinet, Japan's emphasis on Asia and close coexistence with China has emerged as one of the primary features of its foreign policy. This new political entity—evidenced by this visit—is poised to solidify political and economic bilateral ties.

Though widely regarded a party with core conservative values—not unlike those of the LDP—there is also a historically left-wing influence within the DPJ. This, coupled with its longstanding relations with the CPC, allowed it new cooperation with China.

It is worth noting that DPJ officials are far younger, compared with those of the LDP. Most of them possess clear political concepts and agendas and are able to express their ideas more candidly than their LDP counterparts.

Friendship and cooperation have long been bywords when it comes to Sino-Japanese relations, of course. Still, more exchanges between Chinese and Japanese politicians—indeed, as well as people of all walks of life—are needed, so communication can be heightened.

The biggest threat to Japanese diplomacy, according to Ozawa, lies in relations with Washington. He has long criticized Japan as blindly following the United States. Instead, he has noted, Japan needs to pay greater attention to Asian countries—in particular, China, given its ascendance on the world stage.

By heading the delegation, Ozawa has also shown his political prowess. Following the elections, his support within the DPJ has surged, expanding his political faction to be the largest within the party.

More broadly, many members of parliament—and members of the delegation, for that matter—owe their seats to Ozawa's strategic maneuvers.

By bringing this group to China, Ozawa has demonstrated his ability to transcend ideology by heightening Sino-Japanese friendship for the sake of Japan's younger generation.

The author is secretary general of the Center for Sino-Japanese Relations Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences |