|

There was an extra buzz in Beijing's National Agriculture Exhibition Center in mid-February, as young and old poured in to appreciate a show dedicated to traditional Chinese crafts.

|

|

COVER UP: Craftsman Xu Xueming teaches a visitor how to paste handmade oilpaper on the bamboo main frame of an umbrella | During the two-week exhibition (February 9-23), the largest of its kind since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, more than 100 successors of the country's intangible cultural heritages showed off their exquisite skills of various traditional crafts on site. The displayed crafts cover a wide range of traditional skills in China, including casting, weaving, dyeing, paper making, printing, brewing, pottery making, sculpture, embroidery and traditional medicine.

A battery of camera flashlights and gasps of awe were heard throughout the exhibition hall as visitors marveled at the skillful craftspersons and their works. Many older visitors were reminded of their youth by the crafts on display. Crowds who were taken along a historical trip of homegrown creativity surrounded each of the show's stands.

|

|

MIAO MAGIC: Wang Aban works with liquid wax as she demonstrates the batik skills of the Miao ethnic group to visitors (WEI YAO) |

|

|

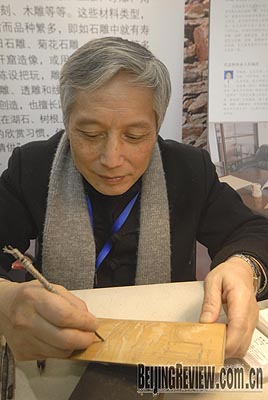

STEADY HAND: Qiao Jinhong busies himself carving another bamboo art masterpiece at the traditional crafts exhibition in Beijing (FEI YAO) | Liu Yanqi, a postgraduate at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was among the curious visitors. "I am a student majoring in the study of traditional arts and crafts in China, so this exhibition is the best chance for me to know the current situation of these cultural legacies," Liu told Beijing Review. "It's so lucky that our ancestors have left us such rich treasures, and I think we should try our best to preserve these and pass them down."

Survival of skills

Liu's remarks are echoed by many Chinese concerned with the survival of traditional crafts, as the social environment on which these skills depend has changed a lot with the advancement in science and technologies. Sadly most of the articles that are made using these traditional skills have lost their function in modern life.

For example, waist daggers that were popular with some minorities in China in the past have gradually lost their practical value, so the dagger-making skill is on the verge of extinction.

This is a common difficulty faced by Chinese craftsmen in passing down and further developing their traditional skills.

Oilpaper umbrella making is another example. In the past, this kind of umbrella was popular, especially in south China. But, with the development of science, they have become nothing more than a kind of decorative art.

Xu Xueming, 42, the sixth generation successor of Fenshui oilpaper umbrella making, with a history of over 400 years in Fenshui, a township in southwest China's Sichuan Province, feels pressure to hand down this craft.

"In the past, people felt proud of using Fenshui oilpaper umbrellas, but now modern umbrellas are more popular," Xu said.

According to him, it takes one week and needs more than 90 steps to finish an oilpaper umbrella. Oil paint ensures the vellum paper umbrella canopy retains its shape and color in sunlight or in the rain. The unique skill of making such umbrellas is that all the bamboo strips that compose the mainframe are connected with five-color silk thread and sewn through over 2,000 times.

|