|

|

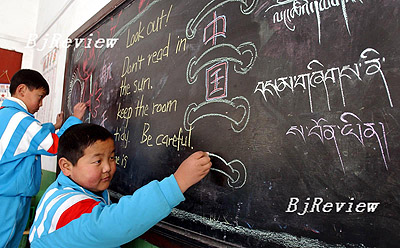

TRILINGUAL: Students from a primary school in Lhasa, capital city of Tibet Autonomous Region, write a blackboard newspaper in Chinese, Tibetan and English (XINHUA) |

When Xu Shixuan, a linguist from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, returned to a southwestern county bordering Myanmar in 2002 to study the local language after a nine-year interval, she was struck by the change to Li Xuewen, a master storyteller in the village. Xu could not relate the silent and listless old man with watery, turbid eyes to her vivid memory of Li reciting tales of his ancestors. When Li's fellow villagers told Xu that a serious illness several years ago had led to the changes to the old man, Xu felt sorry both for Li, and for the human history that could be lost forever before being recorded.

Li is a speaker of the Bisu language, a transnational language spoken in the border areas of China, Thailand, Myanmar and Laos. The Bisu people of China live in Yunnan Province in southwest China. They are a branch of the Lahu ethnic minority. There are around 6,000 Bisu people in China and less than one third can speak their own language. The decline of the Bisu speaking population is also happening in Thailand, Myanmar and Laos, putting the language on the verge of extinction.

Like most of the 82 ethnic languages in China, the Bisu language does not have a unified writing system. The Bisu people's culture has traditionally been passed on through story telling, usually by a respectable senior citizen, during festivals, weddings and funerals, where smart and articulate young men picked up the tales and later tell them to their children.

The fascinating folk tales told by Li, which Xu believed best captured the essence of the Bisu language and history, have provided rich material for her research, which she compiled into a book entitled Bisu Language, published in 1998. "There is no single Bisu person in my research, young or old, who is nearly as knowledgeable about their language and history as Li," said Xu, who still regrets that she failed to record more.

As a linguist who has studied China's ethnic languages for more than two decades, Xu has witnessed the death of numerous languages. Although the demise of a language is in some cases inevitable, she expects that the wakening social awareness of cultural diversity and the state's new efforts to protect endangered languages will help to slow the process.

According to a general plan related to ethnic minorities during the period of the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10) released in March 2007, the government will support the collection of materials and studies on endangered ethnic languages and help to set up a national database for all endangered ethnic languages in China. This marks the first time that protection of endangered ethnic languages has been clearly written into a national policy.

Xu believes this is encouraging for China's linguistic academics studying endangered languages, who felt outside of the mainstream 10 years ago. Xu said Chinese linguists were introduced to the concept of endangered languages for the first time at the 15th International Congress of Linguists on the Survival of Endangered Languages in 1992. The first national academic conference on endangered language was held in 2000.

Over the last decade, China's cause of protecting endangered languages has proceeded rapidly as scholars have been awarded research grants from the Central Government, provincial governments, the United Nations, and foreign academic institutions. Xu said her major concern is a lack of standardization in material classification and an overall research plan, which has led to an enormous waste of research resources. The linguist, who is doing a three-year program sponsored by the UK-based Endangered Languages Documentation Program, said China urgently needs to learn about language preservation from advanced countries and set up a national language archive open to all linguistic researchers.

Until recently the focus of China's governmental language policy had been put on popularizing putonghua, a common form of speech with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect and the standardized Chinese characters created in 1955. The policy was designed to smooth communication between people from different regions as the Chinese spoken by the majority Han people, which constitutes 92 percent of the total population, has some seven major dialects and can be divided into hundreds or even thousands of smaller categories. In October 2000, the Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language was released, which demands local governments at various levels and the relevant departments under them should take measures to popularize putonghua and the standardized Chinese characters.

Xu said she thinks it is time for the government to shift the focus from promoting putonghua to preserving language diversity. "As we all know, language is a tool for communication. People tend to select the handiest tool, which is the majority language in terms of communication. People's self-motivation in mastering the majority language has become a worldwide phenomenon, and putonghua is no exception," she added.

She said in her field of research she had encountered an interesting phenomenon among government officials who assisted her research in regions inhabited by minority groups. These government officials, who were from local ethnic minorities, on the one hand complained about the decline of local ethnic culture, while on the other hand teaching their children putonghua or dialects of putonghua rather than their ethnic group's language as a mother tongue. The reason for this was primarily that they believed a good command of putonghua was linked with better education and employment opportunities, especially if the children left the region to seek a life elsewhere. Meanwhile, they believed that learning a local language could hinder their children's ability to learn putonghua. Xu called these parents the "language-filtering generation," whose perception could cause the extinction of a language in the long term.

Xu believes it is a mistake to promote the learning of putonghua against learning ethnic languages. Her long-term studies have concluded that China's most bilingual ethnic groups, including Korean, Bai and Zhuang, have enjoyed economic development levels and education levels higher than the average level for ethnic minority peoples.

Xu expects a lot from the general plan for ethnic minorities released in March, which intends to introduce pilot programs to create a bilingual cultural environment in ethnic minority regions. Xu's opinion was solicited to create a draft for the plan. One intention of the pilot program is to improve bilingual education. For the time being, more than 10,000 primary and middle schools in ethnic minority regions teach courses in 21 ethnic languages. Ideally she would like children in the plan's pilot regions to begin to cherish their native languages and have no difficulty accessing quality education whether they speak putonghua or not.

Spoken and Written Languages in China

The Han people's spoken and written language is the most commonly used language in China, as well as one of the most commonly used languages in the world. Chinese, also known as hanyu or Han Chinese, comprises seven major dialect groups that are composed of over 100 sub-dialects. These dialects are major components of Chinese culture, playing a unique role in the formation and development of the Chinese nation.

Generally speaking, one ethnic group uses one language, but there are those that use two or more languages. These languages, except for Korean and Gin, whose relationships have not been classified, belong to the Sino-Tibetan family, the Altaic family, the Austro-Asiatic family, the Austronesian family and the Indo-European family of languages.

Archaeological findings and research results indicate a total of 57 ethnic minority scripts have been used within the boundaries of China since ancient times, and 22 ethnic minorities in China are using 28 written languages of their own. In China, the spoken and written languages of ethnic minorities are widely used in the fields of law and justice, administration, education, political and social life, and other areas. When important meetings, such as the national congresses of the Communist Party of China and sessions of the National People's Congress and the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, are held, documents of the meetings are available in Mongolian, Tibetan, Uygur, Kazak, Korean, Yi and Zhuang, and simultaneous interpretations in those languages are also provided.

The minority groups of Mongolian, Tibetan, Uygur, Kazak, Kirgiz, Korean, Yi, Dai, Lahu, Jingpo, Xibe and Russian have their own scripts, most of which have a long history. Of these, Mongolians in the Mongolian-inhabited areas use alphabetic scripts, written vertically, while those living in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region use different alphabetic scripts that fit local dialect features. The Dais in Yunnan Province use four kinds of scripts in different areas.

Most Lisu Christians use a Lisu script based on the Roman alphabet, which uses only upper case letters as well as inverted upper case letters. There are also a small number who use syllabic Lisu writing, created by locals. The Va Christians in Yunnan use a Va script based on the letters of the Roman alphabet. Some Zhuang, Bai and Yao peoples use ethnic scripts that are prominently influenced by Han Chinese scripts.

The Mongolian, Tibetan, Uygur, Korean and Yi languages have coded character sets and national standards for fonts and keyboards. Software in the Mongolian, Tibetan, Uygur and Korean languages can be run in the Windows operating system, and laser photo-typesetting in these languages has been realized. Applied software in the languages of ethnic minorities are emerging one after another, and some achievements have been made in research into the OCR (optic character recognition) of languages of ethnic minorities and machine-aided translation.

(Source: China: Facts and Figures 2006) |