| If not for a conversation overheard in Beijing in 1985, The Children of Huangshi (Huang Shi De Hai Zi), which premiered on the Chinese mainland April 3, would never have been made.

The poster of The Children of Huangshi (Photo from sina.com)

James MacManus, the scriptwriter and then a Beijing correspondent for The Daily Telegraph, was at the British Embassy Club on holiday when he heard a young diplomat complaining about traveling to a remote town in Shandan, Gansu province, because the Chinese government had erected a statue for a British man named George Hogg.

MacManus saw a potential story. In his book Ocean Devil: The Life and Legend of George Hogg, he recalls what he saw then: Deng Xiaoping had begun the economic liberalization that set China on the path of today's market economy. Businessmen from around the world arrived on every flight. Nevertheless, the idea that China would honor an unknown Englishman seemed preposterous.

He pieced together the full picture after research and interviews about the Englishman. It turned out to be an engaging saga.

Hogg came to war-haunted China in the 1930s and embarked on a mission of educating, nurturing and escorting some 30 children over hundreds of miles. He died in China in 1945.

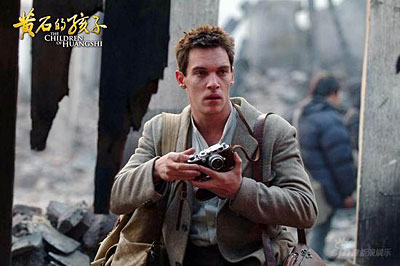

MacManus' story in the Los Angeles Times soon attracted a list of agents, producers and directors, who fell in love with the British man's adventure. Yet, it was not until 22 years later that the story finally hit the big screen - a joint production of China, Germany and Australia. Roger Spottiswoode, who directed Tomorrow Never Dies, helmed the $40-million project, while rising Hollywood actor Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Asian superstar Chow Yun-fat and Michelle Yeoh lead the cast.

For Spottiswoode, it was just the right story. Although born in Canada, he went to school in England, where he learned much about World War II.

"What made this story compelling to me perhaps is that George Hogg was so young, that he had set out from a sheltered, middle-class home in England and he had been so courageous and adventurous in the war," he told China Daily. "And as I listened to what they remember of George Hogg, it became apparent that he was such a warm-hearted and generous spirit that he captured the young minds of these children and gave them courage and hope to achieve the impossible."

Hogg was born to a wealthy family in Harpenden, Hertfordshire. Both of his parents were pacifists. Influenced by his mother's Quaker pacifist philosophy, he set out on a world journey after graduating from Wadham College, Oxford. He crossed America riding the rails, and was to meet his aunt Muriel Lester, a famous pacifist, for a trip to Tokyo, some sources say, or to meet Gandhi, according to others. But on the way, Hogg decided to make a stop in Shanghai, a city then controlled by Japanese forces.

The 23-year-old arrived in Shanghai in 1938, in the aftermath of the Japanese massacre of some 300,000 citizens and soldiers in nearby Nanjing.

The cruel contrast between the wrecked city and the life full of beer, champagne and bonfires in Oxford made the idealist stay. He worked as a reporter for AP in Shanghai and was expelled by the Japanese, after which he made a trip back to China via Korea.

Hogg later worked as an "ocean secretary" or publicity director for the Chinese Industrial Cooperative Movement (CIC), a nationwide organization which trained young refugee labor in technical skills useful in the war against Japanese aggression.

Rewi Alley, a New Zealander writer, reformer and one of the initiators of CIC, described Hogg to MacManus as "a happy board-shouldered young giant in a shirt, shorts and sandals with the bearing of a forward in a rugby pack, and an outstanding young English man who fell in love with a foreign people and devoted his life to their betterment."

Hogg got to know many communists and common Chinese people living in the war's shadow. It was in 1942 that he found his real destination, a small town named Shuangshipu in Shaanxi province. He was named the eighth headmaster of a CIC school there, at 27.

It was barely a school. There were no books or writing materials, classrooms were three brick houses and dormitories were yet to be built. His students were a mix of illiterate peasant children and those from wealthy families driven from the coastal cities by the Japanese troops. But as MacManus said in his book, it was as if everything Hogg had experienced before had prepared him for the task of disciplining, schooling and nurturing a group of unruly Chinese war orphans.

With the help of local workers, he turned a nearby cottage into a dormitory. He taught the boys English, played basketball and swam with them. Until today some of the children, now over-80 seniors, can still sing the songs Hogg taught them.

Nie Guanghan, 76, remembers Hogg as a saint. "They all say there is no perfect man in this world, but Hogg was," he told China Daily. Nie can speak fluent English, partly thanks to what he learned from his "Western Dad."

Nie and his three brothers all lived with Hogg in the school after losing their parents. The youngest brother Nie Guangpei, 69, was only 6 then, and was one of Hogg's favorite boys. Although he heard many details from his brothers later, what he recalled about the war was not that terrible, thanks to the love and care of Hogg.

The happy days did not last long, however. As the Japanese advanced west, Hogg decided to move the whole school to Shandan in Gansu. The over 700-mile trek was a risky decision, in view of the January winter in west China, the mountainous roads, the Gobi desert, and the potential attack from bandits and the Japanese.

The journey on foot and seven mule carts was even harder than they expected. One cart toppled into a valley. Fortunately, when they arrived at Lanzhou, Gansu province, the local official supplied them with six trucks. After another month of trekking over the ice and snow, they finally arrived at Shandan and settled down in a ruined temple.

They rebuilt the school, re-started the cotton-milling machine Hogg liked very much and opened classes again. It seemed everything was going to be fine, until in July Hogg fell sick.

It is said that he got tetanus after injuring his foot when playing basketball with the boys. Two boys were sent by motorbike to find a doctor and serum, but the mountains delayed their journey. When they got back, a funeral was being held for their headmaster.

While bringing Hogg's life on the big screen, Spottiswoode and one of the producers, Wieland Schulz-Keil, made slight changes to add to the drama. Shuangshipu, where Hogg started his career as a headmaster, was a name Western audiences could have found hard to remember, so they chose Huangshi in central China's Hubei province, which has a similar pronunciation. They also changed Hogg's journey, which started in the 1940s, to the late 1930s, right after the Nanjing Massacre.

"From his books and diaries we learned that the massacre, although he did not see it personally, was the most important thing driving his later years," says Schulz-Keil, "so we put the story closer to 1937 when it happened to make the story more compressed. Besides, the massacre is still not that well-known to many Western audiences, and this could be a good way to inform them of what happened."

(China Daily April 4, 2008) |