|

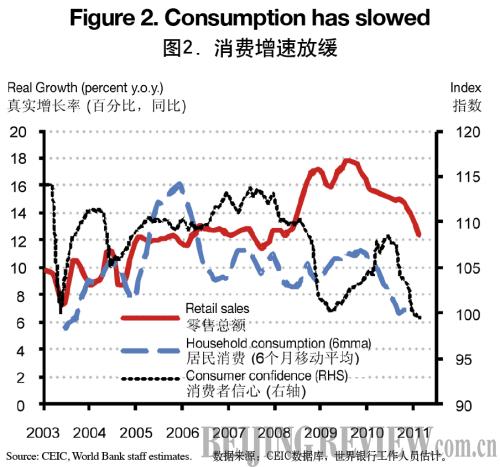

l In all, we project real GDP growth to slow to 9.3 percent in 2011 and 8.7 percent in 2012. The upgrade to the 2011 forecast, compared to November 2010 and March of this year, is on the back of the stronger than expected outcomes in the fourth and first quarter.

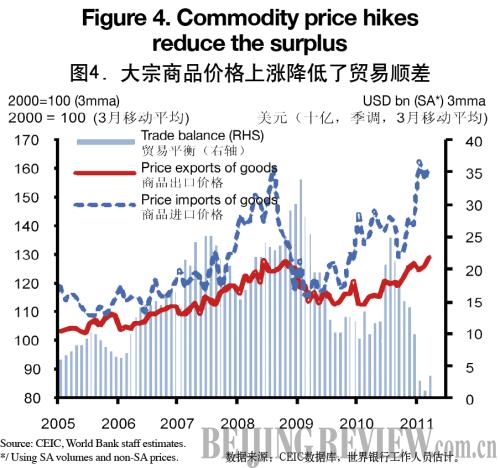

Inflation is unlikely to escalate but there are risks. Food price increases seem to have slowed for now, sequentially, and the (y.o.y) rate of increase in food prices is likely to diminish later in the year (Figure 8). Upstream price pressures may continue to build because of the hikes in oil and industrial commodity prices. Importantly, however, so far core inflation pressures remain in check. Based on the above global price outlook, we expect the moderation in food price inflation in the coming 12 months to more than offset the rise in non-food inflation, resulting in a slowdown in headline CPI inflation, with the pace of deceleration in part depending on factors such as the possible adjustment of some utility prices. Meanwhile, we have revised downwards our projection for the current account surplus because of the higher commodity prices, which affect China's terms of trade substantially.

Domestic risks add to the global ones noted above. Downside risks to growth stem from possibly weaker corporate sector investment or household consumption. However, both also carry upward risk. Higher raw commodity prices pose a risk to the inflation outlook.

The property market is a particular source of risk. With tension between the underlying upward housing price pressure and the policy objective to contain price rises, interaction between the market and policy measures could lead to a more abrupt than planned downturn in the real estate market. In the medium term, the widespread use of property as investment vehicle and the role of local governments add to the risks. Property construction is an important part of the economy, directly and in terms of impact on large sectors such as steel and cement. Thus, shocks to the property sector that would slow down construction significantly could have a large impact on the economy and on bank balance sheets, taking into account bank exposure to construction and other sectors dependent on the real estate market. Moreover, a property downturn could affect the finances of local governments, which do a lot of the infrastructure investment and are important clients of the banking system.

Looking further ahead, whether the recent trend towards a lower external surplus and lower dependence on external trade will be sustained remains to be seen. The fall in the external surplus and the relative importance of exports since 2007 was in no small part because of the global crisis. Whether the domestic economy and imports will outpace exports in the coming five years depends on China's policies, including progress with rebalancing, and other domestic and international developments. If China's domestic demand growth remains much stronger than elsewhere and significant rebalancing takes place, the external surplus may remain contained and the economy may continue to become less dependent on exports. The importance of exports may decline especially if domestic prices continue to rise much faster than tradable prices, as in 2005-10. This would over time change the nature of China's economy, making it increasingly domestic demand driven. It would also facilitate a broadly benign further integration of China's economy in the global economy. However, the tentative results on the pattern of investment across sectors discussed in Box 2 suggest such a scenario is not yet entrenched. With less progress on rebalancing, less benign scenarios are also possible.

Economic policies

The macro stance needs to be normalized fully to address macro risks including inflation and the property market. Even though our baseline inflation projections are not particularly worrying, the risks, including from further global commodity price shocks, call for vigilance. Also, inflation expectations are high, and there is little spare capacity in the economy, overall. Macroeconomic policy remains key in limiting the spill-over of higher prices of food and other raw commodities into other prices and wages and containing other risks, including in the property market and with respect to bank balance sheets. To address such macro risks, macroeconomic policy is typically better placed than moral suasion and administrative measures.

Recent economic policy has largely been moving in this direction. Fiscal policy appears not to provide stimulus anymore and the monetary stance has moved towards normalization. The government has recently also limited the transmission of higher oil prices in domestic fuel prices used moral suasion. [11] Such measures could create distortions and are unlikely to be effective for a long time. With the central inflation outlook manageable, it may not be necessary for concerns about inflation to hold up for long price changes needed for the transformation of the growth pattern such as price increases for resources and utilities.

Looking ahead, it is too early to stop the macro tightening, while, with risks both ways, fiscal and monetary flexibility is key. The strong recent growth has shown the resilience of the economy to the policy normalization. If the slowdown materializes and inflation eases, the case for further overall monetary tightening weakens. However, even then room remains for interest rates to play a larger role, relative to quantitative targeting.

On the property market, market-related risks require one set of policies and social concerns another. After the 2008-09 stimulus, the authorities rightly reined in liquidity, flanked by specific measures, to stop housing prices from surging. However, in general, given robust income growth and urbanization, housing prices should rise over time and empirical research is inconclusive as to what extent prices are systemically out of line with fundamentals. The role of economic and financial policy is to prevent different types of economic and financial risks from building up in the housing sector, including those discussed above, and to make the economy and the financial system robust to a potential property downturn, rather than focusing mainly on containing overall prices. In any case, if overall prices are considered to be systematically too high from a market perspective, macroeconomic levers are most obvious; administrative measures are less obvious, especially locally administered ones.[12]

On the other hand, making housing more affordable for targeted groups requires sustainable rules-based arrangements, almost unavoidably explicitly subsidized by the government. The planned scaling up of social housing discussed below is in this direction. As elaborated below, a transparent, rule-based, financing model is key.

What will be the focus of structural reforms? The 12th Five-Year Plan discussed below has two overall objectives: transforming the pattern of growth towards more emphasis on consumption and services and moving up the value chain in manufacturing. What the 12th Five-Year Plan implies for the way China will grow in the medium term will in part depend on the relative emphasis on these two objectives.

Fiscal policy and public finance

The overall fiscal stance in 2010 probably withdrew stimulus. The commitment budget deficit for the national (central and local) government was 1.6 percent of GDP, down from 2.8 percent of GDP in 2009. However, with 0.7 percent of 2010 GDP in local government spending carried over from 2009 into 2010, the cash deficit was 2.3 percent of GDP last year, compared to 2.0 percent in 2009. As in 2009, the social security funds ran a surplus of around 1percent of GDP. Their operations did thus not affect the fiscal stance. Data on infrastructure lending in the first 9 months of 2010 suggests that quasi fiscal activity financed by bank lending withdrew stimulus in 2010, likely more than offsetting the small increase in the cash budget deficit.

Among budgetary expenditures, priority areas saw significant increases in 2010. As usual, budgetary revenues grew much faster than assumed in the budget prepared in early 2010, with overall tax revenues rising 23 percent and indirect taxes increasing particularly rapidly.[13] Overall budgetary expenditures rose 17.4 percent, somewhat faster than assumed in the budget. Following substantial increases in earlier years, budgetary spending on education, health, and social security—a focus of policy—rose 18.5 percent in 2010, reaching 6.6 percent of GDP, 1.1 pp of GDP more than in 2007 (Table 5). Spending on pensions, health, and unemployment by social security funds and budgetary spending on the environment, agriculture, and "other social welfare" also rose as a share of GDP in 2007-10, while expenditure on social housing increased especially rapidly last year, from a low level.

The 2011 budget is cautious. It sees tax revenues growing at 8.3 percent, which implies a large buffer according to our revenue growth projection, which is twice as high. Budgetary expenditure is envisaged to rise 12 percent this year, with spending on education, health, and social security up 14 percent, less than (our projection for) nominal GDP growth. The broadly unchanged allocation for social housing, with respect to 2010, is surprising, given the drastic increase envisaged in the scale of social housing construction (see below). The budget deficit of 1.5 percent of GDP (using our GDP forecast), compared to 2.3 percent of GDP in 2010, appropriately suggests some withdrawal of fiscal stimulus, with the low estimate of tax revenues providing a buffer and thus some flexibility.

The government has indicated some plans for public finance reforms to support the transformation of the pattern of growth. The Government Work Report for 2011 mentions: a pilot to impose VAT on some producer services industries while reducing the sales tax on them; extending the coverage of the property, resource, and consumption taxes; reforming the pricing of electricity and water; and reducing and simplifying the personal income tax (PIT) by raising the tax exemption threshold, reducing the number of brackets and regularly indexing the structure to inflation. The Report also suggested giving provincial level governments more leeway in setting local taxes to "align better their revenues with their expenditure responsibilities." Most of these would be welcome steps.[14] However, for some of them it is not clear how concrete the plans are and what the time schedule for their implementation is.

Scaling up social housing is rightly used to help transform the economic growth pattern and improve people's livelihood. Social housing construction started along with China's housing reform in the late 1990s.[15] But it declined in importance during the last decade. However, the building of subsidized rental housing and renovation of industrial and mining shantytowns was scaled up in recent years as part of the stimulus policies. One objective of the 12th Five-Year Plan is to construct 36 million units of social housing (including shantytowns renovation) in 2011-15, to give access 20 percent of urban households by 2015, compared to about 7 percent now. The plan is frontloaded, envisaging the construction of 10 million units in 2011, compared to an estimated 3.7 million units in 2010.

Successful, sustainable social housing requires strong institutions and clear rules, including a sustainable financing model and the funding of the subsidy element. Local governments have so far typically not had strong incentives or means to build a lot of social housing. This time the increased prominence of the plans and the Central Government's emphasis provide an incentive. However, the large scale and time pressure, and already stretched finances of some local governments, suggests that the execution may not be straightforward. As the related policies are rolled out, it will be important to define "low income" and carefully identify the targeted beneficiaries, cost out the policies, apportion the financing in a sustainable and transparent fashion, and work out implementation details. The success of these policies will be determined by such details. In the government's plans, of the 1.4 trillion yuan in overall investment required this year, 800 billion yuan would come from the owners (end users or companies involved in shantytown renovation) and around 100 billion yuan from the central government. The rest will need to be generated by local governments via various channels, including land revenues, housing provident funds, and bank lending. The exact structuring of the financing will be hugely important for sustainability and efficiency.

Monetary, financial, and exchange rate policy

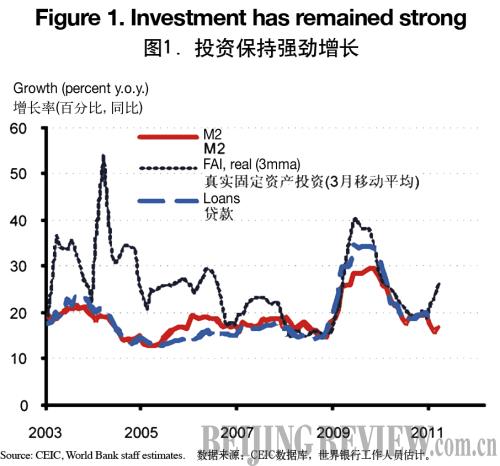

Monetary conditions have tightened recently as monetary policy moved towards normalization. Since October 2010 the government has raised benchmark interest rates four times and reserve requirement ratios (RRRs) seven times. Most importantly, quantitative guidance on bank credit, traditionally the backbone of monetary policy tightening, began to be reinforced, especially in early 2011. As a result, M2 growth came down from 19.5 percent in the fourth quarter to 16.6 percent on average in the first quarter, close to the target for the end of 2011, with a similar slowdown in bank lending. In recent years, total bank credit extension has been significantly larger than headline data suggest as banks expanded the use of credit instruments such as designated loans, trust loans and corporate paper, financed in part by trust and wealth management products that are not counted as deposits and are not part of M2, in order to evade lending quotas, capital requirements and RRRs (Figure 9). This remained the case in the first quarter. Nonetheless, and regardless of the coverage, banking credit extension was tightened in the first quarter of this year (Figure 10). [16] Also, reflecting tighter monetary conditions overall, interest rates on the interbank market have risen since end 2010 (Figure 11).

Recent changes in the operation of monetary policy and a new concept do not imply a change in approach. In early 2011, the PBC introduced differentiated RRRs; so far they are largely differentiated between large and small banks. There is no official overall lending target anymore. However, the PBC still has an implicit target and this change does not imply a major shift in approach. The PBC also introduced the concept of "Total Social Financing" to map the different sources of financing of investment (and to show that containing bank lending does not necessarily imply investment weakness). In addition to headline bank lending it includes the other types of credit mentioned above as well as direct financing through equity and bond issuance. It should be interpreted with care, though. Items such as equity and bond issuance are not new liquidity creation. Also, Total Social Financing would not lend itself well to quantitative targeting.

Over time, a larger role of interest rates could make the conduct of monetary policy more effective and less distorted. As underscored by the proliferation of non mainstream credit extension, it is increasingly difficult to effectively lower credit growth using quantitative guidance in the increasingly sophisticated and complex financial system.

The 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15) was launched earlier this year. It is in line with the proposal circulated in October 2010 that was discussed in our November 2010 China Quarterly Update. In terms of strategic direction and reforms, two areas of emphasis stand out:

l Rebalancing. The government wants to transform the pattern of growth towards more emphasis on consumption and services to address imbalances with regard to the income distribution, the consumption share, the environment, energy consumption, and external balance. It also focuses on livelihood issues and regional rebalancing, with more emphasis on urbanization in inland regions and smaller cities. Such rebalancing obviously requires strong policy effort.[17]

l Industrial upgrading and moving up the value chain in manufacturing. The emphasis is on technological upgrading, investment in "new strategic industries", and innovation. The Plan discusses the role of the government in leading the industrial upgrading and promoting the development of new industries. However, in most market economies, the role of the government in pursuing such objectives would largely be to provide an enabling framework. Enterprises will have to do most of the upgrading and innovation. In any case, given the track record of China's industrial sector over the last decade, industrial upgrading is likely to continue.

Policy-wise, it is important to find the right balance between these 2 areas of emphasis. By itself, industrial upgrading would boost investment and industry. If government policy emphasizes industrial upgrading rather than rebalancing, there might be little change in the pattern of growth, keeping it investment and industry driven, with limited progress towards a higher household income share, a larger role of consumption, and a lower external surplus.

With regard to the Five-Year Plan's growth targets, the challenge is to make them binding and consistent nationwide. The target of 7 percent average growth during the 12th Five-Year Plan period seems appropriate, allowing for relatively rapid growth while creating space for meaningful progress on restructuring. However, under past Five-Year Plans GDP growth far exceeded the targets while no obvious attempts were made to meet them. Also, nearly all provincial governments have set much higher growth targets for their own 12th Five-Year Plans. The challenge now is to make the announced growth rates the true targets behind future policies, and to achieve greater consistency between the policy stances at central and sub-national levels.

The targeted 4 percentage points of GDP increase in the share of services is ambitious but supported by policy proposals. Welcome proposals include establishing fair, regulated and transparent market access rules; breaking up sector segmentation, regional blocks and industrial monopolies; opening more service sectors to private and foreign investors; and establishing an integrated, open, competitive and orderly services market. Other policy measures proposed in the Plan include extending the VAT to services, allowing services firms to enjoy the same utility prices as manufacturing firms, and improving the service sector's access to land and finance.

The targeting of wage growth at or above GDP growth is new. Its motivation is welcome: to halt the decline in the shares of labor compensation in primary income and household disposable income in GDP. It is not obvious whether and how the government should directly influence wages in a market economy. However, pursuing more labor intensive growth and more permanent urbanization would boost these shares in an economically sustainable way.

Reforms of inter-governmental fiscal relations will be crucial for achieving meaningful progress on a range of other policy priorities. China's sub-national governments are responsible for the bulk of spending on public services and infrastructure. Local governments in poor areas tend to be financially strained and there are large disparities in the provision of public services that amplify regional income inequality. During the 11th Five-Year Plan, general transfers to poor provinces have increased, and this has reduced the disparity in public expenditure across provinces. The 12th Five-Year Plan shifts the focus to the sub-provincial level and proposes to increase provincial governments' fiscal transfers to county governments. However, it does not propose specific measures on how to reform inter-governmental fiscal relations, including on the role of the central government at the sub-provincial level. In addition, it would be good to bring the off-budget borrowing by local governments onto their budgets and set up more transparent modes of financing of local government deficits.

Barriers to labor mobility may require more attention. The Plan rightly identifies increasing non-farm income as key in raising rural incomes. It also proposes to relax the barriers for rural migrants to obtain an urban hukou in medium and small towns. However, it does not fully address the removal of barriers to labor mobility otherwise. Also, while the Plan rightly discusses enhancing pension and health insurance to rural people, the continued separation of rural pension and health insurance schemes from urban ones add barriers to labor mobility. Finally, among the recent measures aiming at containing housing prices, in many cities the purchase of property by people that have worked or lived there for less than a certain amount of time was banned. This has not been helpful to labor mobility.

Notes:

[1] In early 2011, the NBS increased the threshold of projects covered by the FAI data and expanded the coverage to FAI by rural enterprises and institutions. It noted these steps did not affect the estimation of investment growth.

[2] The last round included a higher second home mortgage down-payment ratio, higher transaction taxes, restrictions on the number of urban homes people can buy, and increased land supply for public housing.

[3] The current account balance has been revised downwards due to an upward revision of unrepatriated earnings on inward FDI back to 2005, with inward FDI revised up accordingly. In 2009 the revision was 0.7 percent of GDP.

[4] Changes in the CPI weights in early 2011 did not change the estimate of inflation. The weight of food was lowered by 2.2 pp to an estimated 31 percent, and that of residence costs increased by 4.2 pp to an estimated 17.4 percent.

[5] China's wheat and rice prices do not closely follow international ones; they are set by policy. In contrast, China's prices of corn and soybeans do follow international prices fairly closely, and these are both used as feed.

[6] In its first report on capital flows monitoring, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange estimated "hot money" flows at a relatively moderate US$35.5 billion in 2010.

[7] A key reason behind the particularly rapid increase in the GDP deflator is that both the investment deflator and the overall consumption deflator have outpaced the CPI index; the latter largely because of the impact of rapidly rising government wages on the deflator for government consumption.

[8] In 2007-10 the terms of trade worsened in total around 4 percent, which had a modest impact on the change in the current account.

[9] For instance, after the massive expansion in recent years, railway infrastructure investment is envisaged to be broadly constant this year.

[10] As an indication of expected wage dynamics, relative to recent years, according to a survey by Aon Hewitt, a human capital consulting firm, average salaries covered "across all major industries" should rise 9.1 percent this year, compared to 8.4 percent in 2010 and 5.8 percent in 2009.

[11] The NDRC said March 31 it will send inspectors to consumer goods manufacturers to investigate the reasons for price increases and indicated that "some manufacturers will be invited to have talks with the NDRC".

[12] The central government required municipal governments to release targets for housing price increases in 2011 and holds them accountable for their achievement. By the deadline of March 31, most of the cities that had released them targeted price increases of around 10-15 percent.

[13] A 2009 tax reform reduced corporate income tax revenue growth.

[14] PIT is paid by a modest share of the labor force, and by the higher echelons of the (taxable part of) the income distribution. If boosting wage earners' disposable incomes and reducing income inequality are the objectives, reducing social security charges—which are paid by many more people—may be a more obvious measure.

[15] Social housing includes "economic housing" and apartments sold below market prices, subsidized rental housing, and the renovation of shantytown housing.

[16] There has been a methodological change in early 2011 that affected the monetary statistics. However, in contrast to some reports, this did not affect the measurement of M2 growth. The way that designated deposits and loans are booked changed for non bank financial institutions, which reduced the measured amount of both deposits and loans. However, the (yoy) growth rates reported for deposits and loans are adjusted for the methodological change and thus correct.

[17] For an elaboration of the reform agenda for rebalancing, see the World Bank China Quarterly Updates of June 2009, March 2010, and November 2010.

|