|

Private Sector Development

The private sector will remain critical for achieving China's development objectives over the 12th Five-Year Plan period and beyond. Private sector firms are more productive than SOEs and are crucial for job creation.[8] Expanding the role of the private sector has been part of China's reform strategy. However, there is a feeling among many that in recent years the policy stance has favored SOEs over the private sector (see Box in our June 2010 Quarterly Update). At any rate, there is wide agreement that a vibrant private sector is key for raising productivity and for China's further development and growth.

In order to boost the strength of the private sector, in the next five years, China could address the following three challenges:

First, opening up to private enterprises sectors so far dominated by state-owned firms. In 2005, the government expounded the principle of allowing private firms to enter some industries previously reserved for SOEs and called for the equal treatment of SOEs and private companies. In practice, the principle proved hard to implement and progress was limited. Earlier this year, the government issued guidelines that reiterated the desire to stimulate the private sector and remove entry barriers to private investment.[9] The objective is to encourage private investment in sectors such as infrastructure, utilities, financial services, logistics, and defense. Specific measures are still pending.

In this connection, the government could usefully clarify the role it envisages SOEs to play in China's economy. Without a clear, specific policy framework and support, such guidelines may not be very effective, since traditional habits among local governments, enterprises, and banks are sometimes hard to change. Moreover, the guidelines seem to conflict with other explicit principles emphasizing the need for a strong role for SOEs, as codified in a list of "strategic" and "basic or pillar" industries where state-owned companies are meant to play a key role. The current list of "basic and pillar" sectors in industry includes machinery, autos, IT, construction, steel, base metals, and chemicals. If the aim is to stimulate the private sector, it would be useful to reconsider the composition of this list. In addition, there is ample room to open several services sectors to private sector participation.

Second, continuing to address investment climate constraints. During the 11th Five-Year Plan, the overall investment climate for the private sector has improved, notably through the reforms of the regulatory environment to encourage new entry. However, some remaining institutional and policy constraints that hamper the development of the non-public sector could be tackled during the 12th Five-Year Plan. These include:

- Making access to finance more equal and developing capital markets. Despite improvements in the capital market, especially the establishment of the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise (SME) Board and the New Ventures Board, many private firms still have difficulties accessing bank loans and the capital market. This is particularly so for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in the central and western regions, where the relevant financial markets and products are relatively underdeveloped. Thus, an important task during the 12th Five-Year Plan is to strengthen financial services to MSMEs, especially those in the interior regions.

- Adjusting the role of the government and reducing "red tape." Local governments often maintain tight control of economic development, including selecting industries and planning industrial transfer. As part of the process to change the role of the state, the government—including at the local level—could increasingly withdraw from direct intervention in the economy. In this way red tape could also be reduced.

- Reducing further regulatory barriers to entry. Despite the encouragement of private sector development, many sectors still have unnecessarily high barriers. These include unduly high levels for required registered capital and fixed assets.

Third, supporting the research and development (R&D) and innovation capacity of the private sector. During the 11th Five-Year Plan period, the overall innovation climate for China's private sector has improved and some very innovative private firms have emerged. However, most R&D in China is still conducted by large and medium-sized SOES, with private firms, particularly small ones, playing a small role. The government can further strengthen the private sector's innovation capacity through: (i) better protection of intellectual property rights; (ii) helping improve the skills of private sector workers; (iii) strengthening interactions between the private sector and knowledge institutions; and (iv) providing supportive services.

Reducing energy intensity—challenges and policies

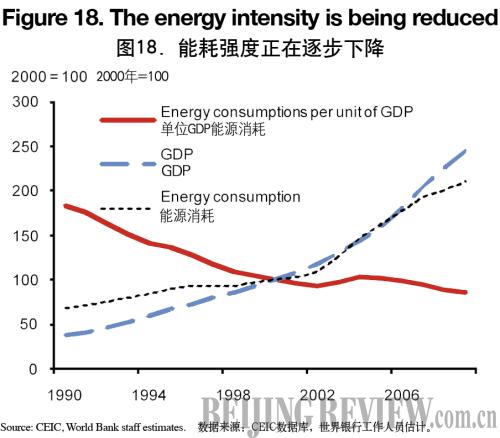

China will get close to meeting the energy intensity (EI) target of the 11th Five-Year Plan. The plan included a target to reduce the amount of energy per unit of real GDP by 20 percent between 2005 and 2010. Using the most recent energy consumption and GDP data, EI was reduced by 15.6 percent in 2005-9. Given developments so far in 2010, it will be difficult to meet the 20 percent target exactly, barring further data revisions.[10] Nonetheless, China will get close, thus decidedly reversing an earlier upward trend in energy intensity (Figure 18). Moreover, the adoption of a binding target has clearly established energy conservation as a top priority at all levels.

More generally, China has made impressive achievements in energy conservation and renewable energy during the 11th Five-Year Plan period. Several reforms have taken place, including in pricing and taxation. Many inefficient coal-fired power plants and energy-intensive factories have been closed. Since the Renewable Energy Law of 2006, wind power capacity has been doubling every year and China has transformed itself into a world leader in renewable energy.[11] These developments have shifted the economy towards a more sustainable energy path.

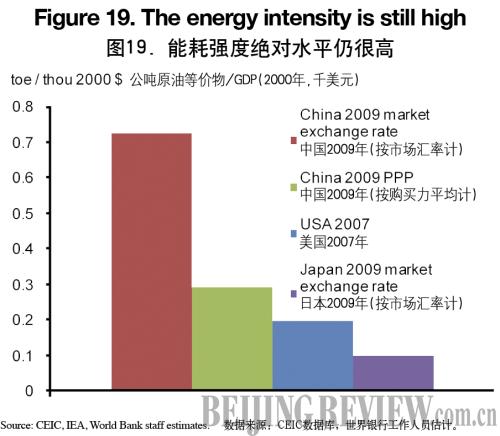

Looking forward, China will continue to face (local and global) environmental sustainability challenges to meet the energy needs arising from rapid economic development. China's energy use per unit of GDP in 2009 was around 3.6 times as large as in the United States and 7.3 times as high as in Japan if GDP is measured at market exchange rates (Figure 19). If GDP is measured at PPP, China's energy intensity in 2009 was around 1.5 times as high as the U.S. level.

Specifically, China's energy needs will be shaped by its response to three overarching challenges. These are: (i) maintaining rapid economic growth while rebalancing the country's economic structure and moving towards a less energy- and carbon-intensive economy; (ii) achieving rapid urbanization while shifting toward less energy- and carbon-intensive cities; and (iii) improving the quality of life while shifting to a less energy-intensive and more sustainable lifestyle. It is essential to meet these challenges to avoid being locked into a highly energy-intensive structure and to contribute to a sustainable energy development path both locally and globally.

In addition to economy-wide reforms to promote rebalancing, meeting these challenges will require actions in four key dimensions of the energy sector:

First, continuing energy pricing reforms. Passing the full economic cost of energy supply to consumers and gradually internalizing environmental costs in energy prices can help increasing energy efficiency, discourage energy waste, and encourage clean fuels. The pricing of coal and oil products now reflects developments in international oil prices in a relatively transparent way. However, fuel prices in particular are still low. The strong international evidence on the link between prices and energy intensity shows China can reduce the energy intensity by raising energy prices further. Pricing reforms are also still needed for natural gas and electric power, building on the welcome recent electricity pricing reform for residential electricity tariffs. Furthermore, introducing meters in district heating would help since the current tariffs are set based on the amount of floor area, which weakens incentives to conserve energy. Prices should also increasingly take account of environmental externalities. To that end, local (and even global) environmental costs can be incorporated in energy pricing through an additional fossil fuel tax and/or a carbon tax.

Second, complementing administrative measures with market-based mechanisms to further reduce energy intensity. Sustaining the reduction of energy intensity achieved under the 11th Five-Year Plan will require: (i) increasing the use of market-based mechanisms and financial incentives while strengthening the implementation of administrative measures; (ii) continued structural reforms towards a less energy-intensive economy while pursuing technical and managerial energy conservation measures; and (iii) strengthening energy conservation in urban buildings and transport while consolidating efforts on large state-owned enterprises and expanding to other enterprises. Enhanced market based mechanisms, such as piloting energy saving certificates trading, developing market-based financing mechanisms, and scaling up the energy efficiency service industry, can also motivate enterprises to implement energy efficiency measures and allow government agencies to play a more indirect supervision role. To this end, the energy intensity reduction target for the 12th Five-Year Plan could be made more customized than the current one (which called for a similar reduction for all parts of the economy). This target can be complemented by a range of investments in human capacity, strengthening incentives, financial innovation, transparent supervision, data collection, reporting and verification methods.

Third, reducing cost and improving performance of renewable energy. Currently, power consumers pay an average of about 0.4 fen/kwh for the higher costs of renewable energy. With the rising share of renewable energy in the power mix, in the absence of a government subsidy, a continued increase in the surcharge for renewable energy may create financial burdens on consumers. In addition, a large share of wind power cannot get onto the grids, biomass development has run into fuel supply issues, and solar PV is still costly. Sustainable growth of China's renewable energy industry would need to focus more on driving down costs while promoting high efficiency and high quality. To address some of these issues, the government has already revised the Renewable Energy Law. Further reforms during the 12th Five-Year Plan period could include: (i) improving renewable energy planning, allocation of mandatory quota, and piloting renewable energy certificate trading; (ii) strengthening feed-in tariff schemes; (iii) resolving the grid integration bottleneck to wind and solar development; (iv) developing policies for distributed generation and integrating renewable energy into power sector reform; (v) accelerating hydropower development; and (vi) improving the performance and reducing the costs for wind and solar PV.

Fourth, accelerating development and diffusion of new energy technologies. Deploying advanced technologies on a large scale requires accelerated and enhanced research, development, and demonstration, coupled with an adequate carbon price. The clean technology revolution offers an opportunity for China to leapfrog to the next generation of new technologies, such as Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC), carbon capture and storage (CCS), electric vehicles, energy storage, distributed generation, and smart grids. Coupling a technology push (e.g. increasing R&D) with demand pull (e.g. increasing economies of scale) is critical to drive substantial cost reductions of advanced technologies. This also provides an opportunity for China to create local manufacturing industries and drive down costs to becoming global technology leaders. China already has three of the top ten global solar manufacturers and its wind manufacturing industry is also on its way to become a global leader. The largest barrier is the high incremental costs between these technologies and conventional options.

Notes:

[1] The household survey data from the urban and rural surveys is weighed up to obtain an economy-wide estimate.

[2] The input output tables suggest only slightly higher increase in ULC for the whole economy during the recent decade, whereas the flow of funds data suggests a 20-percent increase.

[3] "The Cost Competition of the Manufacturing Sector in China and India, an Industry and Regional Perspective," the Conference Board and Growth and Development Center of the University of Groningen, January 2009.

[4] These large wage increases reflected a strong rebound in the labor market after an earlier downturn last year when wage growth slowed. Looked at over a two-year horizon, wage growth is not far from historical norms.

[5] Seasonal patterns suggest export volumes and the trade surplus tend to be substantially higher in the fourth quarter. Our forecast for 2010 simply assumes that, in seasonally adjusted terms, export volumes decline 1 percent per month in the fourth quarter and import volumes rise 1 percent per month on this basis. On prices, we project a deterioration in the TOT of 4 percent in the second half, compared to 15 percent in the first half, as commodity price increases have slowed while export prices have recovered somewhat.

[6] In January-September 2010, the surplus was 2.3 percent of GDP. But the average surplus in the first 9 months was 3.4 percent of GDP in 2007-09, while the whole-year balance ranged from +0.6 percent of GDP in 2007 to -2.8 percent of GDP in 2009.

[7] This is the first adjustment to interest rates since December 2008, when they were cut as part of the stimulus package.

[8] OECD Economic Survey: China 2010.

[9] Several Opinions on Encouraging and Guiding the Healthy Development of Private Investment

[10] The government announced that in the first half of 2010, the EI rose by 0.9 percent, compared to a year ago. Achieving the 5.2 percent reduction in 2010 that is necessary to meet the 20 percent of the 11th Five-Year Plan would require a 10 percent reduction in the second half, compared to a year ago.

[11] In 2009, China added 14,000 mw of new wind power generation capacity, the largest increase in the world. Total installed capacity is expected to reach 30,000 mw in 2010, second to the United States. |