|

Fiscal and monetary policy

China's headline fiscal position remains sound, which helps to provide policy space. Despite the massive fiscal expansion, the headline fiscal deficit reached only 2.8 percent of GDP in 2009, as much of the expansion was financed by bank lending. In the first three quarters of this year, headline expenditure rose 20.6 percent, with fairly even growth of spending across different categories. Revenues increased 22.4 percent in this period, with indirect taxes rising faster than direct taxes. These trends suggest a further reduction in the headline fiscal deficit, although such trends may not necessarily be a good predictor of the whole-year balance.[6] China's official government debt was a modest 17.5 percent of GDP at end 2009.

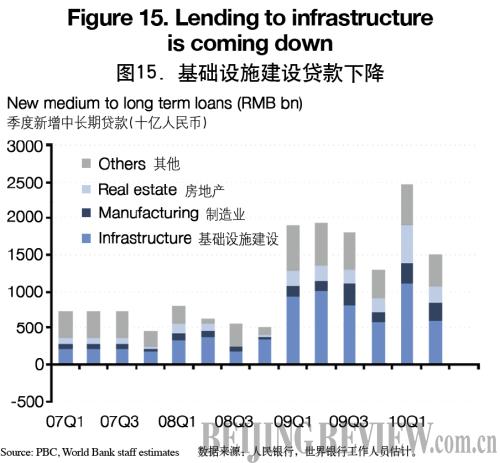

Quasi fiscal spending is being contained, after the surge that has reduced the overall macro policy space. A significant share of the surge in lending to local government investment platforms (LCIPs) since end 2008 may go bad. After an investigation, the China Banking Regulatory Commission estimated in July that of the 7.7 trillion yuan in lending to LGIPs, about 1.54 trillion yuan, or around 20 percent, faces default risk. Given China's solid macroeconomic and fiscal position, and the reported capital cushion of most banks, the local finance problems are unlikely to cause systemic stress fiscally or for the banking sector. Nonetheless, the flow of new lending to the platforms during the stimulus was unsustainable and, overall, China now has less macro policy space than in 2008. The measures taken by the government earlier this year to stem the flow seem to have achieved results. Medium and long term lending to infrastructure—which overlaps with lending to LGIPs—declined from 1111.2 billion yuan (up 19 percent on a year ago) in the first quarter of 2010 to 607.5 billion yuan (down 40 percent on a year ago) in the second quarter (Figure 15). It is important to keep this flow contained and reinforce prudential regulation with regard to this type of lending. It would also be very useful to improve its transparency.

The overall monetary stance needs to be normalized to contain the associated risks. In addition to strained local finances, the most important macroeconomic risks are NPLs and prices of housing, equity, and possibly other assets. Moreover, while the inflation outlook does not seem worrisome, the risks to inflation call for vigilance, managing inflation expectations, and monetary policy leeway. With the economy operating close to full capacity overall and the growth outlook robust, further consolidation of the monetary stance is needed.

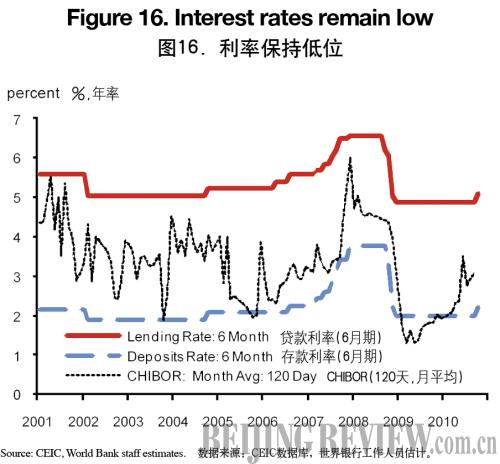

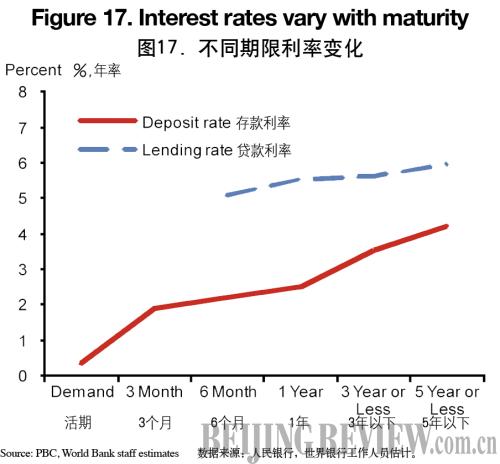

The authorities are broadly on track to meet the 2010 monetary targets and have started to normalize interest rates. Mainstream credit growth decelerated from 33.8 percent in end 2009 to 18.5 percent in September (yoy) and the 2010 target for new lending of 7.5 trillion yuan is broadly in reach. Meeting that target should help manage inflation expectations. However, the case for relying more on interest rates in conducting monetary policy is strong. Off balance sheet credit-type products have grown rapidly recently, in part because of ample liquidity and low interest rates. Reining in such financial activity, and more generally tightening overall monetary conditions, requires higher interest rates as well as containing liquidity in the financial system. In mid October the People's Bank of China (PBC) raised benchmark one-year lending and deposit rates by 25 basis points (Figure 16).[7] The PBC raised longer-term deposits rates by a higher margin, in part to make deposits more attractive relative to alternatives (Figure 17). Longer-term lending rates were raised by a smaller margin. Further normalization of interest rates is needed, as lending and deposit rates are still low relative to historical levels and the buoyancy of the economy.

Pressure from international capital flows may challenge the conduct of monetary policy, but these challenges should be more manageable in China than in some other countries. The abundant liquidity internationally created by loose monetary policy amidst weak growth in developed countries is likely to be attracted by the strong growth in this region, notably China. Such flows will add to the upward pressure on the RMB. However, in China such flows may be less of a problem than is sometimes thought and they should not be a reason not to raise interest rates. The amount of net financial inflows is still quite modest, compared to other flows and domestic credit creation because China's controls on unwanted financial inflows have been rather effective. More than 100 percent of the increase in foreign reserves in 2006-09 was driven by the current account surplus and net FDI while in 2009, the first year with positive net financial inflows since 2004, such net inflows were equivalent to around 4 percent of domestic credit creation.

Measures can be taken to further shore up protection against unwanted capital flows. In current circumstances it makes sense to continue to effectively apply the controls on financial capital flows and also to consider tightening regulation. Earlier this year, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) tightened regulations on overseas lending and borrowing via domestic banks and both SAFE and the PBC announced they would more strictly monitor capital flows. There would likely be more room for further tightening of micro and macro prudential regulation. In addition, more exchange rate flexibility may help in deterring capital inflows, although the recent experience in other large emerging markets shows that flexible exchange rates by themselves may not deter such inflows sufficiently. With regard to the level of the exchange rate, a stronger currency helps reducing inflation pressures by lowering the price of imports and toning down demand. It also helps rebalancing China's pattern of growth toward more services and consumption and less industry and investment.

|