|

Economic prospects

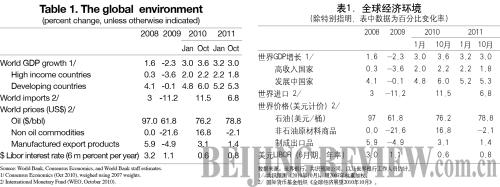

The global economy is starting to slow again, particularly in high income countries (HICs). This is because of an end to the inventory adjustment, implementation of exit strategies for stimulus policies, and sovereign stress in peripheral Eurozone countries and its potential impact on global financial markets. Prospects for growth in the United States and Japan in 2010-11 are being revised downward, which is also leading to further easing of monetary policy there, including possible additional quantitative easing in the United States. Global trade and industrial production are slowing down after the earlier bounce back (Table 1).

However, overall global growth prospects are supported by emerging market strength. In the United States and Europe, the apparent slowdown notwithstanding, mainstream forecasters do not expect a double dip, although the Japanese economy may struggle. Moreover, most emerging markets and developing countries should see continued robust growth. Their growth prospects are of course linked to those in HICs via trade and capital flows, and financial sector risks originating in HICs have global ramifications. However, domestic demand prospects are robust in most large emerging markets, while relatively sound macroeconomic fundamentals buoy the sustainability of their growth. In all, overall global growth prospects for 2010 have been upgraded since January 2010, although those for 2011 have been nudged down (Table 1).

Nonetheless, the global growth outlook remains subject to large risks, both ways. In HICs, households may remain reluctant to consume as they adjust to balance sheet losses and amidst high unemployment and uncertainty. There could also be feedback effects between high public debt burdens, unfavorable growth dynamics, increased rollover risk, and linkages to the banking system. A few factors mitigate downside risks: Private investment may not fall much more, given that it is already low, as a share of GDP, and amidst robust corporate profits; a renewed rundown of stocks is unlikely because inventories appear to be close to desired levels; and overall financial conditions have stabilized in OECD countries, making banks somewhat less reluctant to lend.

The global imbalances and the tensions they create cast a shadow over the global outlook. The combination of large current account surpluses in some countries, including China, and large current account deficits in other countries, notably the United States, poses financial and economic risks, including from possible tension and contentious policy responses to them.

Internationally, underlying price pressures seem to remain moderate, but there are risks. Price pressure remains contained by slack in labor and product markets in HICs and parts of the developing world. In this setting, the prospects for raw commodity prices on international markets including oil and food are considered to remain subdued (Table 1). Discussions on possible renewed easing of monetary policy in HICs, notably the United States, have led to concerns about global inflation pressures. However, the possible monetary easing would be in response to economic weakness. Combined, the associated changes to the outlook do then not obviously imply higher global inflation, although the easing could complicate the financial outlook, including by boosting global liquidity. However, substantial recent increases in many food and industrial commodity prices show how changes in market conditions can affect such prices quickly. More generally, inflationary pressures have resurfaced in several large emerging markets, which are much further advanced in the recovery than the HICs.

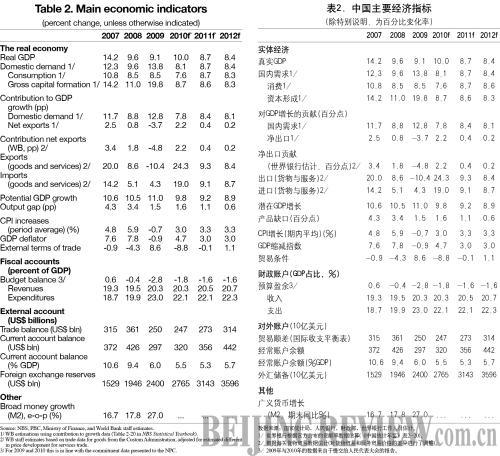

In China, growth may ease in the short term, notwithstanding the surprisingly robust third quarter. The expected slowdown in global growth and imports is likely to affect China's exports. Some additional impact stems from the normalization of the macro policy stance, the eventual impact of the measures introduced to contain property price rises, and some administrative measures to meet energy efficiency targets. Nonetheless, we revise up our GDP growth forecast for 2010 as a whole to 10 percent after the stronger than expected third quarter outcome (Table 2).

Growth is likely to moderate somewhat more in 2011 and the medium term to a still robust pace. The expansion should continue to be supported by the traditional growth drivers and robust macroeconomic fundamentals. In early 2011, activity may also receive a fillip from the end of some temporary administrative measures to meet energy efficiency targets. New public investment programs are also likely to be started next year to accelerate urbanization in inland regions and promote strategic new sectors. However, these are unlikely to fully offset the impact of the end of the 4-trillion-yuan stimulus package. In all, with export growth lower but consumption benefiting from a robust labor market and private sector investment assumed to hold up, we project GDP growth to moderate to 8.7 percent next year. In the medium term growth should remain robust, although trend (potential) growth is likely to diminish. See our June 2010 Quarterly Update for a discussion of China's medium term outlook.

Inflation is unlikely to escalate but it will be difficult to contain housing prices for long. Inflation may remain above the 3 percent target for a while, although the food price increases should eventually decelerate (the domestic supply side factors driving them up are considered largely temporary). Looking further ahead, the inflation outlook benefits from the subdued projections for international prices for oil, industrial commodities and food, recent increases notwithstanding, although China's domestic staple grain prices are not influenced much by international prices. Despite the large wage increases in part of the manufacturing industry earlier this year, core inflation is unlikely to escalate, because China's labor market is flexible and the manufacturing sector appears able to absorb substantial wage increases (Box 1).[4] However, given the fundamental drivers of property prices—rapid urbanization, sizeable income growth, and low interest rates—they are unlikely to remain flat for long.

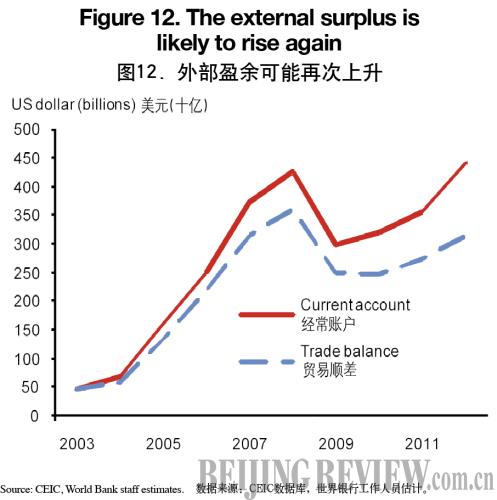

The external surplus is on course to rise again. Taking into account the recent trends in trade volumes, normal seasonal patterns in export and import volumes, and the turnaround in the international terms of trade, the whole-year trade surplus may be broadly unchanged from 2009, because of the low reading in the first half.[5] However, on current policies and trends, the trade surplus is likely to continue to rise in 2011 and the medium term, in $ terms (Figure 12).The current account surplus should rise faster than the trade surplus because the net income on China's rapidly growing net foreign asset position is likely to grow significantly in the coming years. The upward revision in our current account surplus forecast compared to our June forecast is largely because of stronger than expected export volumes and weaker than expected import volumes.

There are of course risks to this outlook. In current circumstances, with the world economy at an inflection point, there are in principle many sources of risk. On growth, the global risks discussed above, including those with respect to global imbalances and possible policy responses, are probably the key ones for China. In this connection, a lack of success in rebalancing China's growth pattern would be among the more serious medium-term risks, for China and the world economy. Upside risks with respect to inflation could arise from further shocks affecting raw commodity prices or from sustained high wage increases driving up core inflation.

|

Box 1.Have Wage Increases Driven up Costs In Manufacturing?

Concerns were raised earlier this year that high wage increases would drive up costs in China's manufacturing sector. Weaknesses and gaps in the data call for caution. Nevertheless, sizeable wage increases in manufacturing over the last 10-15 years seem to have been offset by rapid productivity growth, also in recent years. As a result, unit labor costs fell between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s and remained broadly unchanged since.

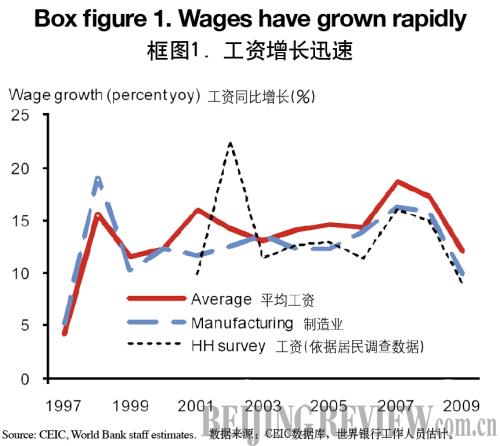

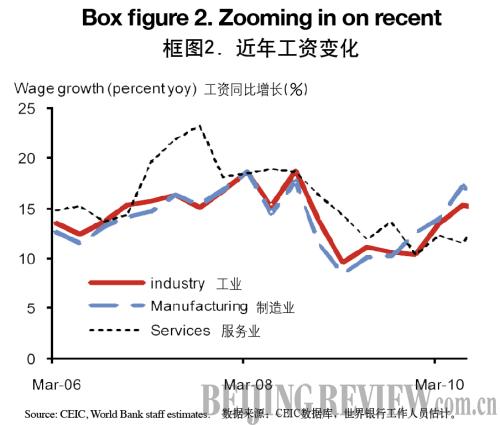

In a booming economy, manufacturing wages have grown strongly in the last decade. Amidst robust urban labor demand, average wages have risen rapidly since 2000, and in recent years wages at the lower end have also started to accelerate. Nominal wage growth picked up further in 2007, when the economy was booming and inflation rising (Box figure 1). However, it slowed substantially in 2009 due to the impact of the global crisis. Quarterly data clearly show the recent deceleration and rebound (Box figure 2). Wages in the services sector decelerated less during the downturn and, conversely, have not seen the rapid acceleration seen in industry since end 2009.

Despite several problems, the wage data provide useful information. The most widely used wage data—used in Box Figures 1 and 2—only cover the urban economy and does not cover most private enterprises. This is in principle a major problem, since it may not be representative for the whole economy. However, surprisingly, this weakness appears not to distort the picture excessively. Separate, independent data from the household survey suggest lower average wage growth than the mainstream data (Box figure 1).[1] However, the household survey data show a similar dynamic and the pace of wage growth is broadly similar to that in manufacturing in the mainstream data. This strengthens the case for using the mainstream data even as caution remains required.

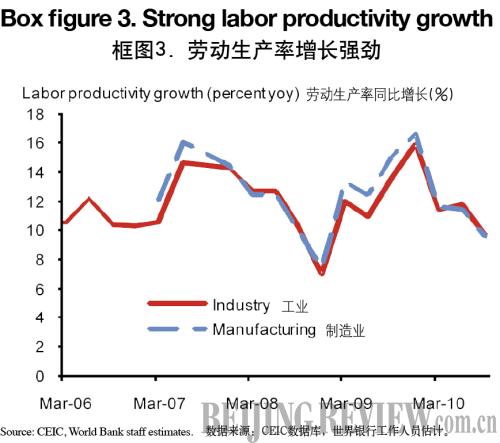

Labor productivity in industry has also risen sharply in the last 15 years. Value added in industry grew at around 9-10 percent in 1997-2001. It then accelerated, boosted by WTO accession and a strong world economy. Moreover, labor productivity was boosted by labor shedding in SOEs: Between 1997 and 2004 (when major job shedding had come to an end), some 43 million SOE jobs, or 40 percent, were shed. According to our estimates, labor productivity growth in industry eased from 15-20 percent in 1997-2003 to still very robust 10-12 percent in post SOE job shedding 2005-2009 (Box figure 3).

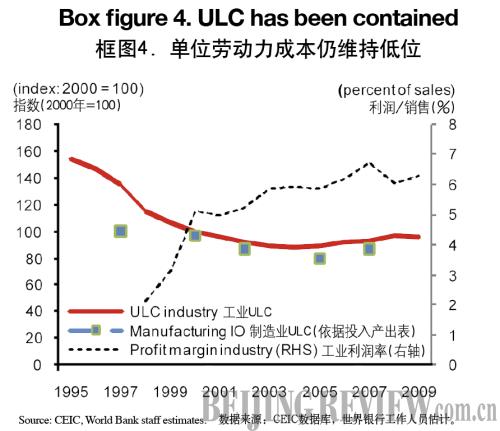

In all, unit labor costs (ULC) in industry seems to have bottomed out in recent years, after a steady decline since the mid-1990s. ULC measures the wage costs per unit of production. Putting together wage and productivity growth, ULC industry first declined, then bottomed out around 2004, and have since edged up slightly. There are several potential caveats concerning this data. However, a ULC estimate from different data source—the input output tables—gives a broadly similar picture for manufacturing, at least from 1999 onwards (Box figure 4).[2] The estimates are also consistent with a finding—on more detailed data—from van Ark, Erumban, Chen, and Kumar (2009)—that ULC in manufacturing fell on average 38 percent between 1995 and 2004.[3] They found that within manufacturing ULC fell particularly rapidly in the machinery, transport and equipment, and electronics sectors, which saw particularly rapid labor productivity growth, and ULC fell less in textile and clothing, where labor productivity had risen less fast.

The suggested broad absence of cost pressures from wage costs in the last five years after a decline earlier on is broadly consistent with data on profit margins in industry. The data, from the industrial survey, suggest that profit margins in industry trended up until 2004 and have remained at that relatively high level since then (Box figure 4).

Internationally, ULC in manufacturing in several other countries nowadays also tends to be contained. For long, since World War II, ULC in manufacturing trended upward in major industrialized countries. However, in recent decades that has not held anymore, because of lower inflation and, presumably, globalization. The OECD estimates that in 2000-09, ULC in manufacturing has declined by 2 percent in the United States and a full 25 percent in Japan, although it rose by 12 percent in the EU and 26 percent in Mexico. |

|