|

|

|

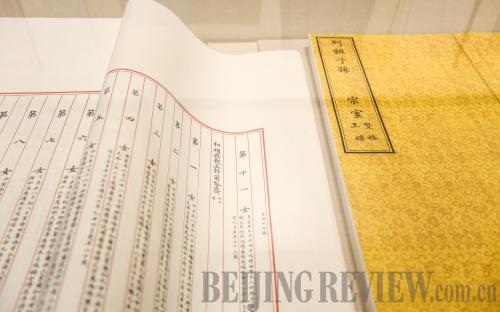

IMPERIAL FAMILY: Qingyudie, a family tree of the royal family of Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), is displayed at the Liaoning Archives Administration on May 2 (YAO JIANFENG) |

Fifty years after the old family tree of the Sun family in Guiyang, southwest China's Guizhou Province, was burned as "feudal garbage," a new version of the family tree was released to the descendants of the Sun family in Guiyang in early May.

"The idea of recreating the family tree was conceived in 2004," said Sun Weihong, a major contributor to the project. "Over the past decade, all living generations of the Sun participated in the compilation. The common aim for us is to rediscover the family history of the Sun and to carry forward our family traditions."

Traditionally, Chinese families maintained family trees in the form of a book, tracing the genealogy, listing male members' achievements and setting out family rules.

However, over the course of history, especially during the wars and conflicts in the early 20th century and the devastating "cultural revolution" (1966-76), many such records were lost or destroyed. The Sun family in Guiyang had not stopped keeping their family tree until 1960s, when the "cultural revolution" began. "I remember there were many ancient artworks in my family, including calligraphy and paintings. But with the surge of the 'anti-feudalist movement' in the 1960s, those treasures were burned," Sun said.

After a series of investigations, the Sun family tree traced back to Sun Qingyan, a local official of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) in Chenggong, southwest China's Yunnan Province.

"It shows that people have realized the importance of knowing their ancestry," said Chang Sixin, former Vice Chairman of the Chinese Folk Literature and Art Society. "Morally corrupt people are not qualified to be inscribed into family trees," Chang said. "People are urged to have good virtues and behavior."

Xiao Fang, an ethnography professor with Beijing Normal University, said that family trees provide a form of cultural identity. "They can arouse a sense of belonging in a time when big families have disintegrated into nuclear families and the concept of family is fading from the modern society," Xiao said.

Tracing roots

In order to revive this nearly lost tradition, some families around the country have started reconstructing their family trees. Compilers include not only senior family members but also many younger ones.

"Traditionally, the older generation would pass family stories down to the younger generation so they would become part of their family spirit," said Zheng Yuguang, Vice Chairman of Shanxi Social Psychology Association.

However, urbanization has separated family members: The old are in the countryside and young are in the cities. "This cuts the connection between generations," Zheng said.

Han Bing is one of the younger generation who is trying to discover his ancestors. Fifteen years ago, he came to Beijing from his hometown in central China's Henan Province. After four years of studying in Tsinghua University and five years of working at a multinational company, he bought his own apartment in 2008 and became a Beijing resident.

"However, after all these years in the city, I still don't feel settled. My parents and sisters live in my hometown. I feel I'm drifting away from my family every day," he said.

Han said he remembers one day when his five-year-old son asked him what his great-great-grandfather's name was. "I had no idea. It surprised me when I found that my father didn't know either." Han decided to make a family tree by himself.

After six months of intense research, including reading files and visiting relatives, Han completed the basic structure of his family tree, covering five generations of the Han family with more than 100 members.

Some young people have also uploaded their family trees onto the Internet to attract more people with the same surname to help contribute.

"The Internet can bring more people with the same surnames together and push forward the compilation of family trees," said Shi Aiwu, a manager of business development at Wojia.com.

Launched in 2008, Wojia.com is arguably the largest online resource for Chinese family histories. It provides subscribers with an extensive collection of digital historical records, based on cooperation between the Shanghai and Hunan libraries and the Shanxi Academy of Social Sciences.

|