| Xinjiang Today |

| Walking Xinjiang into words | |

|

|

He Jianming (left) interviews two embroiderers in Daoxiang Village in Hotan County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, on February 26 (FAN GONGSHEN)

At 69, many writers slow their pace but not He Jianming, one of China's most renowned nonfiction authors. Even after stepping down as vice chairman of the China Writers Association, he continues to produce 4,000 to 5,000 words a day—a rhythm he has kept for decades. For him, the act of writing is a kind of "joyful pain." The pain comes from the overwhelming number of stories he feels compelled to narrate; the joy from witnessing China's transformations, which are too important to leave untold. For half a century, He has been a leading voice in reportage literature, a form of narrative nonfiction rooted in fieldwork and firsthand testimony. His career spans more than 60 books, honors such as China's Lifetime Achievement Award for Reportage Literature, and the distinction of being the first Chinese writer to win Russia's National Book Award. In 2019, he became the first Chinese nonfiction author nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Now, at an age when most writers look back, He is looking ahead—to Xinjiang.  The edge of the Taklimakan Desert in Maigaiti (Makit) County, Kashi (Kashgar) Prefecture, encircled by plants. The photo was taken on March 13 (FAN GONGSHEN)

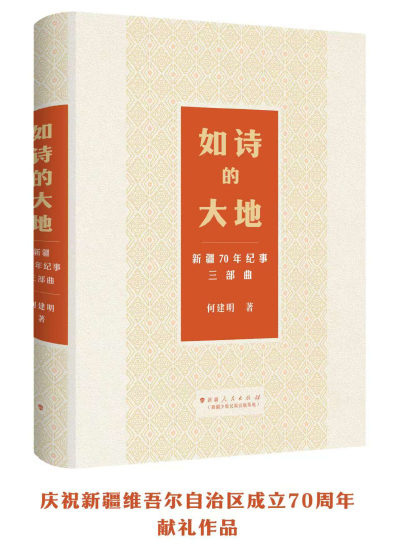

A land transformed He has visited Xinjiang 11 times, each trip deepening his sense of wonder. Between July 2024 and August 2025, He traveled to Xinjiang five times, spending a total of 78 days in the field and speaking with nearly 300 local people in different cities. His notebooks filled quickly with details of new projects in the Kashi (Kashgar) Area of the China (Xinjiang) Pilot Free Trade Zone, the Tarim River Basin, one of the driest and most remote areas in the world, desertification efforts along the Taklimakan, China's largest desert occupying much of the basin, and the construction of an ecological corridor. "The Taklimakan Desert has been encircled with plants. Thousands of hectares of desert have been turned into arable land in just two years," he told Xinjiang Today. The speed of the change still amazes him. As of November 2024, a green barrier more than 3,000 km long had encircled the Taklimakan, becoming the world's longest desert-edge defense system. In addition, an ecological corridor nearly 450 km long has been established along the Luntai-Minfeng Highway that cuts across the Taklimakan from north to south, stabilizing dunes and improving the local microclimate. The regional government encourages residents to fight desertification by engaging them to manage the desert. Managing 1 hectare of desert land alone can bring in 15,000 yuan ($2,100) a year; if a farmer manages 6 hectares, that's a decent income, He said. Xinjiang's green miracles are not limited to deserts. He remembers standing by alpine lakes where salmon swam alongside crabs and even Australian lobsters. Such an improbable scene, he says, was made possible through national preferential policies, financial support and the hard work of Xinjiang people. "Capturing seven decades of Xinjiang's development in a single book is an enormous challenge," he says. But he has already finished the manuscript. Due to be out in late September, A Poetic Land: A Xinjiang Chronicle in Three Parts will be his second book about Xinjiang. In 2022, He crossed Tacheng Prefecture in north Xinjiang, visiting four counties and three cities. He gathered stories of Uygur, Han, Kazak and other ethnic groups building better lives together, and of ordinary people protecting China's vast borderlands. From these materials came his first book on Xinjiang—Pomegranates Blossom. The book takes Xinjiang's pomegranate—whose seeds are sweet, abundant and tightly clustered—as its central image. Each seed symbolizes one life, and together they embody ethnic unity. In 2024, the English translation of the book was named as one of the year's "internationally influential translations" by China Publications Going Global program of the China Publication and Promotion Association. "If Pomegranates Blossom is a small diamond, then A Poetic Land: A Xinjiang Chronicle in Three Parts is a mountain of gold," he said. And he has still more to write about: "I probably have at least three more years of Xinjiang writing ahead of me. Because besides what I've finished, I've gathered so much more."  The cover of He Jianming's new book A Poetic Land: A Xinjiang Chronicle in Three Parts (COURTESY PHOTO)

The making of a writer Born in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province in east China, He began his literary journey due to a stroke of luck. At eight, he found a tattered, coverless book on a relative's desk and devoured it without knowing the title. Months later, he discovered it was How the Steel Was Tempered by Soviet writer Nikolai Ostrovsky (1904-36). The story of Pavel Korchagin, based on Ostrovsky himself, who overcomes immense hardships to become as resilient as steel, left a permanent mark on He's mind. In high school, He's essays won first place across Suzhou. Later, he joined the army in 1976, where his gift for words took him to the newsroom as a military reporter. In 1978, he published his first nonfiction novella Adventures in Western Hunan and his path as a professional writer unfolded. "The charm of reportage lies in reflecting China truthfully, but also artistically," He said. To him, the essence of nonfiction is being close to real people, real life. On his most recent Xinjiang trip in March, he traveled 6,000 km in eight days. The days were spent interviewing people, the nights on the road. More than once, he reached an interviewee's home at midnight. The journeys were not without mishaps. He suffers from high blood pressure, and on one expedition his vehicle became stuck in the Gobi Desert. It left him with a splitting headache and breathing difficulties. But such ordeals, he says, are worth it. "Getting firsthand material is the mission of a nonfiction writer." Unlike many contemporaries, He rarely relies on recorders. He prefers handwritten notes and memory. "My notebooks are just a fraction of what I remember. The most important things stay naturally in my mind, and they return when the moment demands it," He said. While honored at home, his Nobel nomination in 2019 signaled growing recognition of Chinese nonfiction abroad. But he remains grounded in a simple principle: "A good work must first move the writer, then countrymen, and then the world." Chinese writers, he insists, have a duty to tell China's stories with honesty and depth. "When I share Xinjiang's stories, even readers in China are often stunned. That is my responsibility, my mission." Facing AI He is often asked about artificial intelligence these days. His view is blunt, "AI already surpasses 80 percent of ordinary writers," he says. "Type in a few keywords, and in seconds it produces a fine poem or essay." But he also sees its limits. "AI writing about Xinjiang will only be superficial. It cannot accumulate lived experience or speak with the voice of someone who has been there." For him, the antidote lies in individuality. "Literature and art must remain personal and unique. That is how we withstand AI's impact." In an era when algorithms can churn out passable prose in seconds, he continues to write the old-fashioned way: traveling, observing, listening and recording with pen and memory. He still walks through deserts and mountain passes in Xinjiang to witness change firsthand. This persistence is not nostalgia. It is conviction. For him, truly moving words cannot be generated by code—they must come from lived experience, from the pulse and breath of real life. And so he keeps writing—recording Xinjiang, and China, with his steps, his pen and his life. Comments to linan@cicgamericas.com |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|