| Voice |

| Zero-G, Zero Rules: The Wild West of AI in Space | |

|

|

|

At the Third Deep Space Exploration (Tiandu) International Conference in Hefei, Anhui province, on September 5, Wu Weiren, chief designer of China's lunar exploration program and a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, revealed plans for the country to conduct a kinetic impact demonstration mission targeting an asteroid. The mission, which will follow a "fly-by, impact and follow-up fly-by" model, will use AI to help execute the operation.

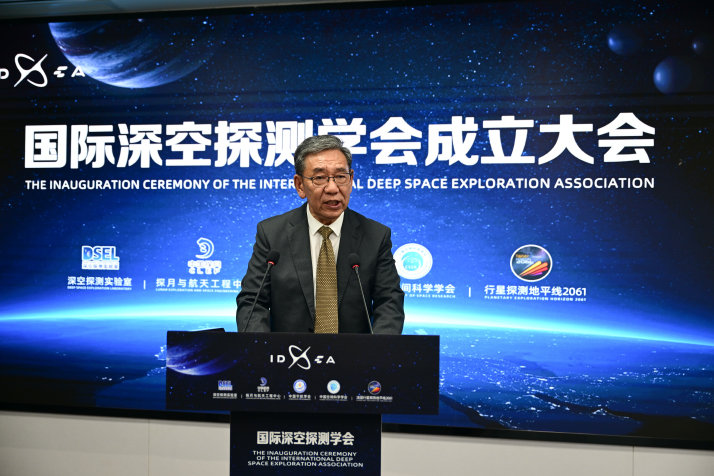

Wu Weiren, chief designer of China's lunar exploration program, who was elected as the International Deep Space Exploration Association's first chairman, speaks during the association's inauguration ceremony in Hefei, Anhui Province, on July 7 (XINHUA)

This is a major step forward in space exploration—but it also opens up a new debate: What happens when AI starts making decisions in outer space? AI promises to boost efficiency in space missions, but it also brings new legal questions into focus: Who should be held responsible if something goes wrong? Who owns the data generated in space? And are the algorithms guiding spacecraft ethically sound? The era of spacefaring AI is here, but the rulebook is still stuck on Earth. The risks There are three main challenges. First is the technology itself. AI often functions like a "black box"—its decision-making process is hard to explain, and algorithmic bias or hardware failures may occur. As a result, a spacecraft could veer off course, collide or create space debris that affects multiple countries. Second is legal responsibility. International space law is clear on this matter: States are accountable for their activities in space, and humans must retain final control. But when AI systems act on their own, are they just tools, or more like agents? That grey area makes it hard to apply existing treaties, like the Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1967 and considered the "Magna Carta" of space law, to real-world incidents. Third is fairness. Not every country has the same level of expertise in AI or access to space data. Those with advanced technology could dominate decision-making, leading to what some call "digital hegemony." That would clash with the principle that outer space is the shared heritage of humanity. Smaller spacefaring nations worry that without clear mechanisms for equitable participation, the benefits of AI in space will be captured almost exclusively by a handful of powerful states and corporations. International space law hasn't kept up with the times. Most of it is still built on the Outer Space Treaty—long before AI was even imagined as part of spaceflight. For example, the Space Liability Convention—which was adopted in 1972 and offers a clear, international framework of rules and procedures for assigning financial liability when a space object causes damage, injury or loss of life—says, "A launching state shall be absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its space object on the surface of the Earth or to aircraft in flight." But what if the damage results from an AI system's autonomous decision, not a direct government order? In that case, victims might struggle to find anyone who bears legal accountability. On top of that, today's legal framework says nothing about the intellectual property of AI models, algorithm transparency, data sharing or ethical standards in space. Many of these questions exist in a legal vacuum. Without new agreements or updated treaties, states risk drifting into a future where accidents, disputes and even intentional misuse of AI in space occur without a clear basis for resolution. Building consensus will require balancing innovation with accountability, ensuring that AI serves as a tool for collective progress rather than a source of mistrust and division in outer space.  A science fiction-themed planetary science experience exhibition at the China Architecture Science and Technology Museum in Wuhan, Hubei Province, on July 18 (XINHUA)

A new framework To meet these challenges, the world needs to act quickly and establish a set of coordinated rules—on both the domestic and international levels. At the national level, China could take the lead by piloting legislation, such as regulations specifically governing the use of AI in space activities. Such rules should clearly define AI as a "tool" under space law, ensure smooth alignment with existing treaties and create a system where designers, operators and states share responsibility. High-risk AI systems in space should also meet strict standards: Algorithms must be explainable, decisions traceable and humans able to intervene at any moment. This would not only help enforce national oversight but also uphold commitments under the Outer Space Treaty. At the international level, a two-step approach may be needed. In the short term, bodies such as the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space could issue ethical guidelines for AI in space, outlining basic principles for its use. In the long term, a binding international treaty could be pursued—one that establishes clear liability rules, compensation standards, data-sharing mechanisms and even a global registry of space AI activities to boost transparency and predictability. Dispute resolution will also be key. Existing institutions such as the International Court of Justice or the Permanent Court of Arbitration could be expanded to handle AI-related space cases, supported by a panel of space law experts, AI engineers and ethicists. This body could gradually build standards for evidence and causality in cases where AI systems cause damage. Beyond law, ethics must also guide the use of AI in outer space. Four principles stand out: No matter how advanced AI becomes, humans must be able to step in, overrule or take charge; AI-driven space benefits should be shared, not monopolized—through cooperation on data, modeling and talent training; given the fragility of the space environment, any AI-led activity, from debris removal to asteroid redirection, must be undertaken with extreme care; AI decisions must be traceable and auditable—so that if something goes wrong, accountability can be established. AI is transforming how humanity reaches for the stars. But without strong laws, fair international rules, effective dispute mechanisms and firm ethical guardrails, the risks could outweigh the rewards. By taking the initiative now, China can both safeguard its own interests and help shape a more just, inclusive and sustainable system of space governance. Only through law and cooperation can humanity truly—and safely—journey into deep space. Xiao Junyong is executive director of the Research Center of Science and Technology and Human Rights, Beijing Institute of Technology; Li Dinggen is an assistant research fellow at the center Copyedited by Elsbeth van Paridon Comments to dingying@cicgamericas.com |

|

||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|