| Lifestyle |

| Modern Opera Reverberations | |

| Exploring the contemporary existence of traditional Peking Opera | |

|

|

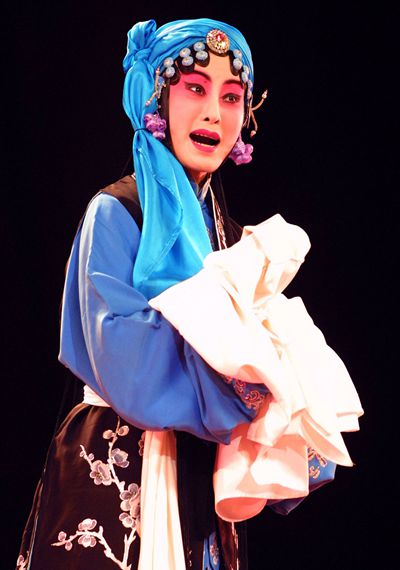

Zhang Huoding performs in the play of the Jewelry Purse (CFP)

"Zhang Huoding! Zhang Huoding! Zhang Huoding!" Legions of young fans, waving and clapping hands, yelled out the name of their idol among crowds at the Chang’an Grand Theater in Beijing on May 24. This was not a pop concert, but a Peking Opera show—a traditional art form in China that has a history spanning over 200 years. It has nonetheless seen a recent decline in popularity as it continues to lose younger generations of followers—but not in some cases. There was a short period of suffocating silence just as Zhang was about to come out on the stage. Unlike the audiences' frenzied behavior, the opera actress walked out at a leisurely pace. After several graceful movements, she made a pose in time with the final tone of the background music. The applause swelled with continuous exclamations of "excellent!" The fans had good reason to be excited. When the show's tickets were released online on May 13, they were sold out within two minutes. Some fans, knowing the chance to attain tickets online was slim, formed long overnight queues at the ticket office of the Chang'an Grand Theater. "This is no surprise at all," said Wei Qun, a 38-year-old Beijing banker who has followed Zhang for 10 years. In an interview with Beijing Review, he said that when he started to follow her in 2006, she was already very popular. "Now, it is just getting crazier. Today it is almost impossible for me to get a ticket for her performances." The Zhang fans in the audience went wild repeatedly during the show. At the conclusion, scores of young people wielding cellphones rushed the stage from all corners of the house, snapping photos and cheering.

Tan Zhengyan performs a role in the play Ding Jun Shan (CFP) The art of diligence In contrast to a typical celebrity's reaction to success, Zhang maintains an aversion to publicity. She rarely grants interviews and often avoids public appearances outside of her work on stage. Her inaccessibility to the public seems to only burnish her appeal to fans. Those obsessed by Zhang's performances include opera traditionalists and youngsters. Born in 1971, Zhang fell in love with Peking Opera at 9 but failed to gain admission to a regional training academy three times. At the age of 15, relatively late for an opera student, she was finally able to enroll in a school in Tianjin. In 1989, she was invited to join a Peking Opera military troupe, based in Beijing, and began training with one of most accomplished Peking Opera performers, Zhao Rongchen. There, Zhao taught her the Cheng School style, one of the four major Opera styles for female roles, which emerged in the early 20th century. Stardom came some years later, in the mid-1990s when she was performing with the country’s leading Peking Opera Troupe. The opera world then began raving about her for her unique and excellent performance. "When I saw her performance for the first time in 2006, I was totally soaked in the opera world she created for the audience," Wei said. "It was so thrilling that I couldn't stop following her since then." For Wei, everything she saw about Zhang, from the motion of her eyes and face—every physical movement—was just beautiful. "The accuracy of movements is not what performers pursue, as Peking Opera is more about the meaning or feeling that the actors create," Wei said. "She was born for Peking Opera, especially the Cheng style, which features low-pitched, deep, subtle tones which complement her personality." As a comprehensive performing art that combines music, singing, dialogue, pantomime, acrobatics and martial arts, an actor or actress in Peking Opera has to meet more requirements than other forms of performing art. All of these skills are expected to be performed effortlessly. The old saying that a "One minute performance on stage takes 10 years of relentless practice behind the scenes" is apt for the rigors necessary to perform Peking Opera plays. "She's always been very diligent," said Li Jinping, who has worked with Zhang for more than 20 years. "She dedicates most of her energy to her craft and teaching students at the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts," Li said. After giving birth to her daughter, Zhang declared in 2010 that she would leave the stage for a while. She went back on stage in 2014. The four years of absence only seems to have added to her audiences' hunger. Her first show on April 26, 2014, at the Chang’an Grand Theater caused a sensation—a rare sight for modern day Peking Opera performances. In September 2015, Zhang went to the United States and gave two performances—The Legend of the White Snake and The Jewelry Purse, at the David H. Koch Theater at the Lincoln Center, both of which were widely covered by the local media. Despite of all this, Zhang still remains somewhat distant from the public. She has only given terse replies to questions during interviews which she could not avoid. "I don't have much to say," Zhang told Xinhua News Agency. "I love Peking Opera as part of my life. That is it. I hope more people can understand how beautiful the opera is and love this art."

The classic play of Long Feng Cheng Xiang presented by the Peking Opera Troupe of Beijing is staged in Wuhan, Hubei Proinvce, on November 21, 2012 (CFP) The opera family Zhang is an exception to the overall declining Peking Opera market. As an integral part of Chinese culture for over 200 years, Peking Opera originated from humble beginnings in east China's Anhui and Hubei provinces. It was brought to Beijing by Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), who discovered and fell in love with the vibrancy and life in the performances he witnessed during his periodic inspections of the southern regions. As an 80th birthday gift to himself, he ordered local troupes to perform for him and had the Anhui and Hubei groups incorporated into the palace opera. Gradually, several performing masters set out to establish their own schools, preferring to hand down their skills solely to their offspring. Tan Zhengyan, born in 1979, is the only child in the seventh generation originating from Tan Xinpei, the founder of the Tan school—which focuses only on the performance of the senior male role. "Peking Opera has been my family’s only profession for seven generations," said Tan. Blessed with a good voice and being the only son in his family, he grew up under great expectations to maintain the family's tradition. But he admitted that he hesitated to undergo the grueling training, considering Peking Opera’s shrinking market. He is not alone in the younger generation of opera families. Mei Wei, the great-grandson of Mei Lanfang, the founder of the Mei school, devotes most of his time to rock music. Meanwhile, Qiu Yun, the daughter of Qiu school founder Qiu Shengrong, has never received professional Peking Opera training because "it is too hard to be a successful Peking Opera actor now." "I have learned Peking Opera since the age of 10 and done my best to practice and perform, but there are still many flaws in my shows," Tan said. Tan revealed that he had faced sharp criticism from the audience, since he is from a famed opera house and should therefore perform flawlessly, according to them. Tan feels that he isn’t able to surpass his forefathers at all. Despite the complaints, Tan has chosen to continue performing Peking Operas. Apart from practicing in a traditional way, Tan has his own innovative ideas on how to develop them. He once performed with a top Japanese jazz band in 2003, and his shows at the traditional Dongyuan Peking Opera Theater in Changpuhe Park have attracted many young fans. Now, as a leading actor of the Peking Opera Troupe of Beijing, Tan has won wide recognition. "The Tan family is regarded as legendary for handing down their style through seven generations," said Cui Wei, Deputy Secretary General of China Theater Association. "But it also shows that the passing down of this art within a family is quite passive and limited. To spread it and give it a longer life, it is better to jump the fence and expand it to a larger scale." Yu Shumin, a student of Mei Baojiu, the son of Mei Lanfang, said she has never worried about the future of Peking Opera. Guided by Mei, Yu started to teach Peking Opera in primary and middle schools in Beijing since 2008. "The students don’t have to be professional actors or develop it into a career," the 66-year-old Yu told Xinhua News Agency. "We just want them to know more of this art. Peking Opera stories mostly come from our folk tales." Yu is very happy to see that some of her students have fallen in love with Peking Opera and that some have even organized Peking Opera amateur groups after they entered college. In 2013, the Ministry of Education said that operas such as Peking Opera would be added to the primary school curricula as an extracurricular choice in some municipalities and provinces, allowing students the option of enriching their spare time while gaining an appreciation for the vanishing art. On November 18, 2015, after giving a show in the United States, Zhang Huoding set up a training center at the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts to tutor students attempting to master the Cheng School of Peking Opera. "It is our responsibility to pass down Peking Opera, which is renowned as a national Chinese treasure," said Zhang at a press conference after the center’s inauguration. Zhang claimed that she owed her popularity to her diligent training. Unlike Yu’s teachings, Zhang’s center is mainly for professional learners with serious career goals. "Young people today aren’t always willing to put up with the rigors, discipline and sacrifice needed to become a great performer," Zhang said, adding that she wanted to inspire the next generation. "Long before [they went on stage], they’d pour water on the ground on a freezing day and create a sheet of ice and force students to practice their movements on the slippery ice," Zhang said. "If you could move gracefully on the ice, you would be able to do well on stage. Now, if there aren’t carpets in the studios, apprentices would just fall down. This makes it a lot harder to have grandmasters." Li Li, one of Zhang’s students, was about to quit Peking Opera until she met Zhang. "I saw her glory on stage and I also saw her practice hard every day, both of which I thought were stunningly impressive," Li said. "I decided to stay and practice hard."

Copyedited by Bryan Michael Galvan Comments to yuanyuan@bjreview.com |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|