| China |

| A new cinematic exploration of shared experiences and societal shifts | |

|

|

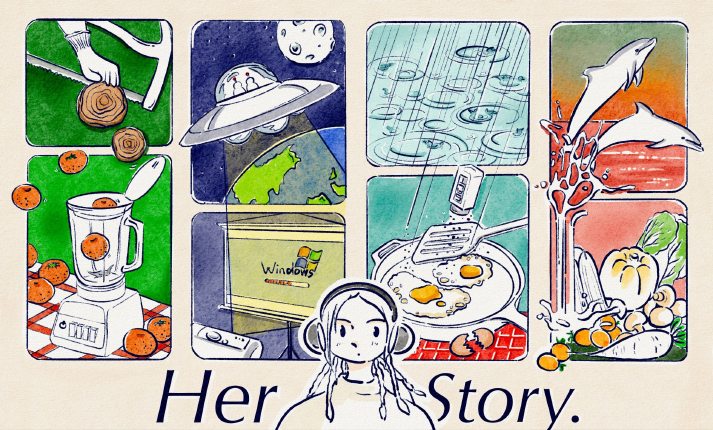

An illustration inspired by the "sound guessing" montage in the film Her Story (VIA TINA_MAO ON XIAOHONGSHU)

'The heroic life is the sphere of danger, violence and the courting of risk whereas everyday life is the sphere of women, reproduction and care," writes British sociologist Mike Featherstone in his 1971 paper The Heroic Life and Everyday Life. Though this perspective today may seem dated, the division of gender roles between public and private spheres remains evident in contemporary cinema. In Her Story, a newly released Chinese comedy film directed by Shao Yihui, however, these traditionally separate spheres are deconstructed and interwoven to form a new kind of narrative. The film follows three women living in an old Shanghai neighborhood: Tiemei, a fiercely independent single mother and a former investigative journalist; Moli, her 9-year-old daughter; and Xiaoye, a foley artist grappling with romantic entanglements and alcohol addiction. One montage in the film zooms in on a guessing game in which Moli tries to guess the source of a variety of sounds that Xiaoye recorded. The child's guesses are: heavy rainstorms, howling tornadoes, dolphins leaping out of the ocean and a rocket launch—dramatic sounds that belong to a world of heroic adventures. Their actual sources, however, are mundane household activities: The rainstorm is the sizzling of frying eggs; the tornado is a vacuum cleaner; the dolphins are tomatoes dropped into a water-filled sink; and the rocket is a computer booting up. This sequence immediately captivated Chinese social media. "These sounds shape our immediate world, but we barely notice them," a comment on Xiaohongshu, China's leading lifestyle platform, read. Director Shao revealed the scene was inspired by childhood memories of her mother squeezing orange juice—a sound she only recognized after it faded from her life. "In a way, the entire film, like this scene, is a collection of small and trivial acts that are neither unique nor dramatic," she told Beijing Review. "But these moments are part of our shared experiences as women—things that are so common yet so rarely seen or heard." Upside down Since its release on November 22, the film has become a major box office success in China. As of December 3, the film had grossed more than 400 million yuan ($55 million) and accounted for more than half of the country's daily ticket sales. The film has also scored a rare 9.1 out of 10 on Douban, a Chinese review platform famous for its harsh ratings, where only an extremely small tribe of Chinese films such as Chen Kaige's iconic Farewell My Concubine (1993) and Zhang Yimou's classic To Live (1994) have managed to top the nine-point bar. The last Chinese film to achieve this feat on Douban was Dying to Survive, a 2018 black comedy about cancer drug imports. Curiously though, the film scores a mere 5 out of 10 on Hupu, an online community where 90 percent of the users are male. Critics on Hupu have loudly opposed the movie's gender role reversals, particularly its portrayal of men vying for women's attention and quoting feminist figures like Chizuko Ueno and Gloria Steinem. This exploration of gender norms is not new for Shao. Her 2021 debut, B for Busy, features a deliberately subversive scene in which only men shop for groceries.  A still from Her Story shows protagonists Tiemei, Xiaoye and Moli work together to change a light bulb (COURTESY PHOTO)

"In a way it is absurd," Shao said. "But I've always pondered the question—should I depict a world that is real but I don't like, or should I present one that I desire but isn't real? And I have chosen the second path." Some netizens have compared the film to Barbie, the 2023 international smash hit directed by American actress and filmmaker Greta Gerwig, in which gender roles are also inverted to let women rule over Barbieland. Yet many argue that Her Story is more than a Chinese version of the pink-filled Hollywood fantasy, given it confronts pressing gender issues in today's Chinese society. A bold move that the film has taken, is its departure from the portrayal of single mothers in Chinese films as tragic characters crushed by social hurdles. Instead, it depicts Tiemei, the single mother, as someone who unapologetically smokes, dates a drummer and does not want her daughter to study too much—blatantly rejecting conventional expectations. "As a woman who has the capacities for self-love and self-fulfillment, Tiemei breaks away from the traditional cinematic representation of women as noble figures put on a pedestal for their self-sacrifices," Zhou Zhou, an associate researcher at the China Film Art Research Center, told Chinese magazine Lifeweek. In Shao's films, the dinner table often serves as the stage where the most confrontational conversation happens. In Her Story, one such pivotal scene centers on another hotly debated theme, the menstrual taboo. The chatter bounces back and forth, touching on the lack of education men receive about the subject, the shame Xiaoye felt when she had her first period and ends with Moli, the only child in the room, declaring, "What is there to be ashamed of when half the world's population shares this experience?" While some critics have likened the dinner scene—and the film as a whole—to a stand-up comedy routine packed with punchy one-liners, Her Story is a testament to how far Chinese cinema has come. "Criticisms are part of a healthy film market," Shao said, noting that the clash of different opinions and perspectives in itself represents progress. History to herstory The rise of Her Story as one of the year's biggest phenomena in Chinese cinema reflects a shifting cultural landscape, where films directed by women and centered on the female experience are finding bigger commercial success and greater emotional appeal.  Behind the scenes with Zhong Chuxi (left) starring as Xiaoye, the film's director Shao Yihui (center) and Zeng Mumei starring as Moli (COURTESY PHOTO)

While women film directors are not new to the set, for a long time, the country's film industry—as is the case in many other countries—was a male-dominated space. "China boasts a stellar lineup of female directors," Dai Jinhua, a prominent cultural critic and professor at Peking University, wrote in a 1994 essay. "However, like Mulan, these women filmmakers often have to disguise themselves as men by hiding their own gender traits and perspectives." The rise of a new generation of Chinese female filmmakers, who are more focused on addressing gender issues from a woman's viewpoint, started only recently with the release of Hi, Mom, a 2021 film directed by and starring comedian Jia Ling. The film, which charts a woman's journey back in time to befriend her own mother, grossed more than 5.4 billion yuan ($740 million) in the country. This feat made Jia the world's highest-grossing women director of all time—a title currently held by Greta Gerwig. At the beginning of this year, Jia dropped another megahit: YOLO (an acronym for "you only live once"), a boxing drama tapping into a range of gender-related issues, from body image to self-empowerment for women. Raking in a whopping 3.4 billion yuan ($467 million), the film remains the highest-earning Chinese film of 2024—at the time of writing. Despite an overall bleak year for the Chinese box office, with total ticket revenue so far down 21 percent compared to last year, a slew of small-budget women-centered films including Remember Me and The Unseen Sister have also made their way to the 100-million-yuan ($13.7 million) club. Within this league, Like a Rolling Stone, a film directed by Yin Lichuan that tells the story of a 50-year-old Chinese auntie's solo road trip across China, earned a Douban rating of 8.8, placing the film alongside all-time classics including Wong-Karwai's 1994 masterpiece Chungking Express and Zhang Yimou's 1991 Raise the Red Lantern. Media scholars believe that this budding of women-focused narratives has largely been driven by a continuous increase in Chinese women's purchasing power. "Women have the ability to explore any facet of the human experience through film," Dai said. "How to create our own mode of cinematic storytelling, and not just a reversal of the male gaze, remains a challenge yet to be addressed." (Print edition title: Telling Her Story) Copyedited by Elsbeth van Paridon Comments to pengjiawei@cicgamericas.com |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|